For sportstats home

page, and info in Test Cricket in Australia 1877-2002, click

here

|

Z-score’s

Cricket Stats Blog The longest-running cricket stats blog on the Web

|

Charles Davis: Statistician

of the Year (Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians)

|

Who are the Fastest-Scoring (and Most Tenacious) Batsmen in Test

Cricket? Click Here. |

Longer articles

by Charles Davis Click Here |

A list of

“Unusual Dismissals” in Test matches |

Unusual Records. For Cricket Records you

will not see anywhere else, Click Here |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

some

remarkable first-class innings, re-scored. |

The Davis Test Match Database Online. Detailed scores for all Tests from 1877 to the 2010s have now been posted.

More than three-quarters of Tests include ball-by-ball coverage; virtually

all others offer some degree of extended detail, beyond anything previously

made available online. The starting page

is here. An information page outlining

this database is here. Major Test

Partnerships (200+) 1877 to 1970. Major Test

Partnerships (200+) 1971 to 1999. |

|||

|

About 150 bowlers have taken a wicket in their

first over of Test cricket, but only Tareq Aziz of Bangladesh has managed to effect a run out. He did so at Gros Islet in 2004. Other

bowlers have seen a run out in their first over (JC Watkins, MA Hanley, SMSM

Senanayake) but they did not receive a run out credit. Aziz did not actually

take a wicket in said over, and only took one wicket in his career, for 261

runs. Four bowlers have taken a catch in their first

over bowling in Test cricket (i.e., a caught & bowled): JA Rudolph JS Patel WW Hinds ******** |

13 February 2026 The recent sale ($A460,000) of a Baggy Green cap worn

by Don Bradman in 1947-48 was the second sale of a cap from that season in

the past two years. Turns out that Bradman was issued with two caps and gave

both away to members of the touring Indian team of that season. Both are now

returning to Australia. It got me looking into the Baggy Green and making

some notes … Australia adopted green caps in 1899. However, the

early caps not “baggy” but were tight-fitting (skull caps) with minimal

peaks. There was a coat of arms on the caps, which is still

used today. Curiously, this is not the coat of arms of Australia (as adopted

at Federation in 1901), but an earlier version. In 1921, the Australian touring team was issued caps

with a looser fit – the “Baggy Green” (although not known by that name at the

time). For some time, these included the motto “ADVANCE AUSTRALIA”, which had

been used even before the myrtle green colour was adopted in 1899. By the

early 1930s, this motto had been simplified to “AUSTRALIA” in yellow on a red

background. The term “Baggy Green” seems to date from the 1950s,

although it did not come into wide use until the 1980s. For several decades, players were issued with new

caps for every series, sometimes multiple caps (such as Bradman’s duplicate

1948 caps). The early ones were undated. After World War II, dates (seasons)

were stitched on the caps; this was discontinued by 1973. Bradman was issued with up to 13 baggy greens. Eleven

are known to still exist. The practice of issuing multiple caps continued up

to the 1980s. Len Pascoe says that he was issued with four caps from 1977 to

1982 (14 Tests). None were dated, unlike the late Bradman caps. Even Steve Waugh was issued with multiple caps. The

one he wore to near-destruction was not his original

Test cap. The ceremonial issuing of caps to new players began

in 1996 (Kasprowicz, Elliott) under captain Mark Taylor. From this point,

only one cap was issued to each player. A near-religious veneration of the Baggy Green

developed under captain Steve Waugh, brought to a new level by a 2003 sale of

a 1948 Bradman cap for $425,000. Allowing for inflation, this remains the

highest price paid for a Baggy Green, with the exception of

Shane Warne’s cap, auctioned for over one million dollars (ironically, only

infrequently worn – Warne preferred floppy hats) in 2020. The price was

amplified by the fact that the money was going to charity (bushfire victims). ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

******** Ian Hill has alerted me to some problems with the

ball-by-ball scores of the 2000 England v West Indies series. This was in the

early days of Cricinfo’s bbb texts. These were not

presented as reliable scores, but at the time they were the only available

source for the data. https://www.sportstats.com.au/zArchive/2000s/2000EW/2000EWcov.pdf ******** |

24 January 2026 Most wickets on the first 2 days of a Test (since 1920)…

Curiously, there were no Tests with more than 30 wickets

on the first two scheduled days between 1912 and 1999. A number of Tests played before 1920, when wickets were poorer

and over rates high, would also feature on this list. These include three

Tests in which the full 40 wickets fell on the first two days, including the

original Ashes Test in 1882 (also Lord’s 1888 and Port Elizabeth 1895-95). ******** In response to a question, I compiled a list of

bowlers whose first over of Test cricket contained a wicket (or two). Turned

out to have exactly 150 names. The list included a few wickets that were run

outs. Most of the data (125) came from ball-by-ball records with 24 names

from the Test Cricket Lists book, from Tests that are not in the bbb

record. (There are also one or two names in TCL that have proven to be

in error, and some of the others may be regarded as unconfirmed). The 150th

name was Keith Miller, who is in neither source but

it now known to have taken a wicket with his first ball in Test cricket (in

the second innings against New Zealand in 1946, having not bowled in the

first innings). Other names from earlier times may yet come to light. Graeme Swann and Richard Johnson took two wickets in

their first over in Tests. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At Perth, England was over 100 runs ahead with

nine second-innings wickets in hand. Yet only two sessions later, England had

lost the Test. How rare is this?... [Conditions: team 2nd innings more than 100 runs

ahead with nine or more wickets in hand. Team is bowled out and loses match,

all on the same day...] Adelaide 2006-07, after Flintoff's (in)famous

declaration at 6/551, Australia 513, England was 69/1 on final day. Out for

129, England lost by 6 wickets. Colombo 2009, Pakistan was 285/1, 135 ahead on

the last day. Out for 320 and lost by 7 wickets.

Subramanyaiah Nallamutla Hanumantha Rao Srinivasulu Nagabhushanam Hanumantha

Rao Surampudi Nethi Hanumantha Rao Sri Nagendra Hanumantha

Rao These four names are all wrong and are completely

made up. Ultimately, Indian umpiring guru Ashru Mitra provided the full name.

It is Sakaleshpur Narayana Rao Hanumantha Rao “Rao” occurs twice; it is not a typo. Narayana

Rao is his father’s name. ******** Their first scoring shot in Test cricket was a

five… Shakeel Ahmed Pak v Zim (2), Bulawayo (Queen's)

1994/95 PR Adams Cape Town 1995-96 BW Hilfenhaus Aus v SAf

(1), Johannesburg (Wanderers) 2008/09 Naeem Islam Ban v NZ (1), Chittagong 2008/09 MD Rae NZ v WI Wellington 2025-26 ******** |

15 December 2025 Yet More Data on Fast Centuries Hundred in a Session in the Fourth Innings of a Test SJ McCabe 189* Aus v SAf

(2), Johannesburg (Old Wanderers) 1935/36 A Melville 104* SAf v Eng

(1), Nottingham (Trent Bridge) 1947 NJ Astle 222 NZ v Eng (1), Christchurch 2001/02 DR Smith 105* WI v SAf

(3), Cape Town 2003/04 Mushfiqur Rahim 101 Ban v Ind (1), Chittagong

2009/10 KS Williamson 121* NZ v SL (1), Christchurch

(Hagley) 2022/23 TM Head 123 Aus v Eng (1), Perth Stadium 2025/26 Prior to Head, Williamson was the only one to do

this for a winning side. Williamson remains the only one to score a century

after tea on the 5th day to win. Speaking of Bulawayo, there is another feature of Wiaan Mulder’s 367 not out in July that I have just

noticed. He scored a century in a session twice in the one innings. He scored

131 after tea on the first day and then 103 before lunch next day. There are

only three precedents: Mulder follows Bradman (334), Hammond (336*) and

Hayden (380). Rachin Ravindra recently scored centuries in a session in

two consecutive Tests, at Bulawayo (once again, poor Zimbabwe!) and

Christchurch. ******** Another Look at DRS LBW reviews. This time including lbw decisions that did not

attract a review. A block of 177 recent Tests was examined. In eleven

of the Tests DRS was not used, so these Tests were excluded. Only Top 6

batsmen were considered. Curiously, the number of batsmen who ended up lbw in

these Tests was actually 553. This takes into account an additional 89 batsmen who were

initially given not out lbw, but the decision was overturned by a bowling

review.

Sometimes batsmen do not review an adverse decision

because no reviews are available, or they are simply in error and might well

have been not out on review. This appears to be quite uncommon, however. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1976 against New Zealand in Karachi, Majid

Khan played one of the great opening innings, reaching 108 runs before lunch

on the first day. There is no full scoresheet for this match, but now Afzad Ahmed has published a book that includes a one-page

linear score (produced by Ben Lawrence) of Majid’s innings;

as a result a full ball-by-ball record of the innings can be built. My rendering of the innings can be found here. There are still only six cases of a century

before lunch on the first day. Majid’s remains the fastest; he reached 100

off 77 balls. A feature of the play is that only 18 eight-ball overs were

bowled before lunch. Only 138 balls were bowled before Majid reached his

century. Even though it was almost 50 years ago, the over rate is very

similar to modern rates. ********

******** I was asked about the unusual case of Indian

captain Ajit Wadekar, who scored 44 and 0 in two consecutive Tests in

1972-73. There are quite a lot of cases of players making identical scores in

two consecutive Tests if you include ducks, although very few involving a

score of 40 or more. Certainly the most notable of

all cases is Harbhajan Singh who scored 63 and 7 at Sydney in 2008, and then

the same at Adelaide. He did not play in the intervening Test in Perth. There are a few players who batted eight times in

four Tests without scoring a run, although all include 0 not outs, including

D Ramnarine and Chris Martin. ******** |

30 November 2025 More Data on Fast Centuries Travis Head’s century at Perth (100 off 69 balls)

has been described as one of the most remarkable in Ashes, coming in the

fourth team innings after none of the previous three had reached 200.

Measured from the start of the (team) innings, Head’s innings was the

second-fastest ever, behind a century by David Warner in 2011-12. A list of

the fastest centuries, measured in balls bowled after the batsman came to the

crease, follows… Fewest Balls Bowled before a Batsman

reached a Century

Well I suppose this is much the same list as the fastest

centuries in balls faced, but it does add a bit of interesting data. The data

is from various sources: no balls may or may not be included. ******** Batsmen benefiting from DRS

overturns.

Latham was given out lbw twice (to Ebadot Hossain) in one over. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First-class cricket at most different grounds

This table is offered with uncertainties. The

identification of grounds is sometimes difficult especially with frequent

changes of ground names. |

12 September 2025 Changing Face of Test Stats It has taken a while, but I have updated the “hotscore” file, showing

the fastest-scoring players in Test history. The update shows the impact of ‘Bazball’, with no fewer than four current England players

hurtling into the all-time Top 20. Travis Head of Australia is another bat

flying high. The Hot 100: The Fastest-Scoring Test Batsmen of All

Time Qualification: 2500 runs for

recent careers. 1,500 runs for careers ending before year 2000. Batting average greater than

20, batting position <7. Updated to September 2025.

If you relax the qualifications quite a bit to

include batsmen with just 500 runs and an average over 15, and include

tailenders, you also get an interesting list… The Fastest-Scoring Test Batsmen (500+ runs) Qualification: 500 career

runs. Batting average greater than 10. Updated September 2025.

L Amar Singh (India 1930s) scored 292

runs at 102 runs/100 balls. The extended lists are found here. At some point

I will try to update the other lists on that page, although there tends to be

little movement in the slow-scoring lists. (The previous list is here.) If you are wondering about the fastest-scoring

batsman of all, without qualification, the Australian fast bowler Jhye Richardson has faced just 14 balls in Tests and

scored 18 runs, a scoring rate of 128 runs /100 balls. His last Test

appearance was in 2021, so he could conceivably play again. ******** There have also been changes at the top in the area of head-to-head, batsman v bowler stats. After

Virat Kohli/Nathan Lyon just failed to take the top spot from Smith/Broad

last Australian season, Joe Root, facing Ravi Jadeja, swept in to pass the 600 run mark. Here is a short

article I wrote on the subject for a magazine. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

29 August 2025 1902 Revisited The

1902 England-Australia Tests still rank among the finest and most memorable

Ashes series. For the statistician, however, it is a frustrating series in

that it is poorly represented by original scorebooks. At the Australian end,

no tour book is known, and in England only one full Test score (Edgbaston)

survives, along with a partial score (lacking bowling details) for the

Manchester Test. Now

there has been some progress, and on a couple of fronts. Simon Wilde has

published a fascinating book “Chasing Jessop” about 1902 and focussing

on Gilbert Jessop’s famed 104 at The Oval, where England won by one wicket.

Using the ever-expanding British Newspaper Archive, Wilde has uncovered some

new sources, a couple of which give ball-by-ball accounts for Jessop’s hundred.

Wilde found the source of Gerald Brodribb’s account, a source that had eluded

me for a long time. It was not in a daily newspaper, but in The Athletic

News and Cyclists’ Journal, a weekly published five days after the event.

Test

1 Edgbaston: reconstructed ball-by-ball from a full scorebook. Test

4 Old Trafford Aus 1st innings reconstructed

by me some years ago from newspaper reports and the partial scorebook. Could

do with more work. Test

5 The Oval: full reconstruction of England 2nd innings by S Wilde. The

cover page for the series, with the updated files, is

here. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A report in the Adelaide Chronicle for the 5th

day of the Adelaide Test in 1907-08 (15th January) claimed that

the temperature reached 111 degrees Fahrenheit (44 Celsius). I wondered about

the accuracy of this, but the Adelaide Register and the Advertiser both gave

an official maximum for the city that day of 111.4 degrees “in the shade and

153 degrees in the sun”. The temperature at Eucla in W.A. was recorded as 122

in the shade (50 Celsius) and “179 in the sun” (!). John Benaud has a book out about the 1973

Australian tour of West Indies: “The First

Ball after Lunch”. There are

a couple of little snippets that show up how cricket, and society, have

changed. Benaud mentions player payments from the time: A$200 per Test plus a

few allowances. Sponsorship was starting to add to this, but not by a lot.

I seem to recall that one of Allan Border’s

children was born while he was batting in a Test. It was one of the only days

of his career where he was dismissed twice. ******** |

Bob Simpson 1936-2025 I saw Bob Simpson play from time to time in the late

60s/early70s. He played in Sydney for Western Suburbs 1st Grade, whose home

ground was near our home. Having retired too early from first-class cricket,

he was still one of the best bats in the world, and he rather terrorised the

Club bowlers. He was one of a cohort of Australians at the time who gave up

the game because of poor pay and the need to make a career elsewhere. My father was a 1st grade umpire and knew Bob. One

day when Wests were playing away and Dad was umpiring

I spent the day watching (getting out of Mum's hair). Bob gave us a lift

home. Dad introduced me. I was too shy to say anything much, but I was most

impressed that Dad and Bob were on a first name basis and chatted all the way

home. My school friend Malcolm Gorham was a cricket (and

Simpson) fanatic. While still at school, he had managed to get a gig as

Western Suburbs scorer, using linear scoring. Malcolm went on to score Test

matches at the SCG, but died (far too young) decades

ago. Simpson famously returned to Tests in 1977 after a

10-year break and scored a couple more centuries. Simpson’s passing on August 15 brings to five the

number of players from the 1966-67 tour of South Africa who have died in the

last few months. I can't find any other cases of five members of a team

passing away so close to one another. The nearest I found was five deaths in

639 days for the South African team that played in Durban in Durban in

1935-36.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The shortening of boundaries, which have been in

place for more than 20 years now, has led to shots for three becoming far

less common. The most in this decade is 45 at Brisbane in 2020-21. There were 85 threes in the Ashes Test at

Adelaide Oval in 1994-95. Of the historical Top 20 where data is available,

ten were at the MCG. At Headingly in 2023, there were no threes at

all. ******** A minor record: Wiaan

Mulder’s 367* at Bulawayo is the highest score by a batsman who was dismissed

by a no ball: previously Warner 335*. Mulder was 'bowled' by LT Chivanga on

247. I believe that Len Hutton was caught in the deep

off a no ball when he made 364, although in those days with the early call it

was effectively a free hit. Most runs added after being dismissed by a no

ball: 279 by Sangakkara (287). Dale Steyn 'bowled' Sangakkara and had him

dropped in the same over. The pair then added more than 600 runs. |

14 August 2025 I thought I'd share an observation about the recent

resurgence in batsmen retiring hurt. The incidence of retirements has jumped

in the last few years. I wouldn’t read too much into each fluctuation in the

figures, but there are definitely some trends.

******** UPDATE of a list from only a couple of weeks ago. At

The Oval, for the second time in the series, the losing side scored more runs

off the bat than the winning side. At Lord’s England had beaten India by 22

runs, at The Oval it was India winning by 5 runs. There had only been four

previous such Tests in all Test history. Winning a Test with fewer runs off the bat

Tests won by runs margin with no

follow-on. In the 1992 match, Sri Lanka managed to bowl 53 no

balls to Australia’s 19, and lost by 16 runs. At the

Oval, England bowled 22 wides to India’s 11 and lost by 5 runs. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Forty years ago (1985) I was travelling around

southern Africa, part of a 5-month round the world trip which also took me to

North America and Europe. It was mostly low budget solo travel - I never

spent more than $20 on a night's accommodation, even in Switzerland - but I

did join small group tours to remoter places like Namibia and Botswana. Since I wasn't completely broke when I got home to

Sydney, I drove up to Cairns and beyond for a bit. Don't ask me why. After

that I WAS completely broke. I have written down a few little memories of that

trip and my other travels last Century. https://www.sportstats.com.au/Travel/Travelslist.pdf ******** Making a Century after being dropped

first ball…

Since 2002 only. The Hussey case is debatable and

may not have been a dropped catch. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Much has been said about records set in the Kingston

Test, with West Indies bowled out for 27. Some adds… The innings saw the slowest over rate in Test

history for a complete innings – around 55 balls per hour (pending a check of

times). One could argue mitigating circumstances. ******** In 1974 Gerald Brodribb published a biography of

Gilbert Jessop (The Croucher) that included a ball-by-ball summary of

Jessop’s famous 104 in the Oval Test of 1902. Brodribb did not name his

source, and over many years I have not been able to locate it. Such

frustration. ********* I try to record fielder locations for all catches

in Tests. In the Lord’s Test, Washington c Brook v Archer was the first catch

by a longstop that I have noted since Tom Horan took a couple in 1879 ! I have often thought that longstop would be a

useful position in T20 with all those ramp shots, but I haven't seen it in

Tests. I don't know if anyone recalls anything similar. ******** Most runs on first day as a Test captain…

******** At Hyderabad in 1983, Javed Miandad faced a

hat-trick ball from BS Sandhu and went on to score 280 not out in a

partnership of 451 with Mudassar. Gavaskar probably faced a hat-trick ball to start

his 236 at Chennai but I don't have enough detail to be sure. None of the

reports I have specifically says so. I only have ball-by-ball data for about 80-85% of

hat-trick balls. If wickets are taken with the last two balls of an over,

then either bat could face the hat-trick ball. ******** |

20 July 2025 I have written before (as long ago as 2006!) about

the intriguing limited-overs match in South Africa in 1967 between the

touring Australians and a “Sports Roundup Invitation XI”, effectively a fully-representative South Africa. Although not

‘official’, it has enough hallmarks of a One-Day International to be

recognised as the first such match (IMHO).

South African XI v Australians, 50-over match,

Johannesburg 4-Mar-1967

Australia

Innings FoW

TR Veivers retired hurt at 5 for 276. South

Africa Innings FoW

The match was 50 (6-ball) overs a side, with bowlers

limited to 11 overs. Although arguably played in a ‘picnic’ atmosphere, there

was money at stake; it was taken seriously enough for the keeper Brian Taber

to be dropped and Simpson taking the gloves to strengthen the Australians

batting. Grahame Thomas of NSW was in the team and scored 70; he had not

played in the Tests, but his mere presence in apartheid South Africa is

interesting in that he was part-aboriginal – especially in

light of the D’Oliveira affair less than two

years later. For the South Africans, the first appearance of Barry Richards

is notable. Keith Stackpole hit a ball from fast man Peter

Pollock clean out of the ground, but was out next

ball. Tom Veivers then came in and appears to have retired hurt first ball;

he did not bowl later. The over eventually cost 10 runs even with two wickets

(Stackpole, Thomas) plus Veivers’ retirement (1 leg

bye, 6, W, RH, 3, W). The match was scored by two women, “Miss P Williams

and Miss SR Hall”. Tour scorer M (Mitch?) McClennan is also named, but the

score is not in his handwriting. (I believe that McClennan was a South

African scorer contracted to score on the tour; he also did 1957-58). An

image of a page from the score is here. I have posted

before an article on

the match by Alf Batchelor. ******** At Lord’s England beat India by 22 runs in spite of hitting fewer runs off the bat. There have

only been five such Tests… Winning a Test with fewer runs off the bat

Tests won by runs margin with no

follow-on. In the 1992 match, Sri Lanka managed to bowl 53 no

balls to Australia’s 19, and lost by 16 runs. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

250 and 150 in a first-class match. Dhruv Shorey, 252* and 150* Delhi v Assam 2022-23 Shubman Gill 269 and 161, Edgbaston 2025 Warwick Armstrong came very close in 1920: 157* and

245 in a Sheffield Shield match ******** At Hyderabad in 1983, Javed Miandad faced a

hat-trick ball from BS Sandhu and went on to score 280 not out in a

partnership of 451 with Mudassar. Gavaskar probably faced a hat-trick ball to start

his 236 but I don't have enough detail to be sure. None of the reports I have

specifically says so. I only have ball-by-ball data for about 80-85% of

hat-trick balls. If wickets are taken with the last two balls of an over,

then either bat could face the hat-trick ball. ****** |

11 July 2025 Here is a broad look at a ‘batting decay curve’, the

number of innings by recognised batsmen (those with median batting positions

1 to 6) at every level of scoring. I have taken the liberty of including not

outs by adding the batsman’s career average to the score (this can be

supported statistically, in a broad sense). So an

innings of 100 not out by a batsman who averages 50 registers as a score

equivalent to 150. Above a score of 50, I have pooled results to smooth

the curve. So the point at 110 represents the

average of scores 106 to 115. The size of the pool is larger at very high

(and rarer) scores. Averaging out at the high end, across a wide pool, can

give values less than 1.

The graph is log-linear because the results are

exponential, with quite a good fit to a simple exponential decay curve (the

trendline is based on data from 15 to 300). Put simply, a batsman’s chances

of getting out when he reaches a given score is about 2.6 per cent, and this

applies, in a broad sense, at all scores from about 20 all the way to 300 or

beyond. Naturally, individual batsmen can and do deviate from this trend, but

the averages are fairly consistent. There are some general deviations, though. That 2.6

per cent probability of getting out doesn’t settle down until a score of

about 15. In particular, There are more than 4200

ducks which represent about 15 per cent of all innings. Between 50 and 100,

the chances of getting out are slightly lower than the long-view average,

while from 200 to 250, the chances are a bit higher. ******** 400 runs in a first-class match without

a quadruple century

[Note: EDITED the Perera instance was left out of

the original table.] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

“Substitute” bowlers taking a

wicket in same over

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

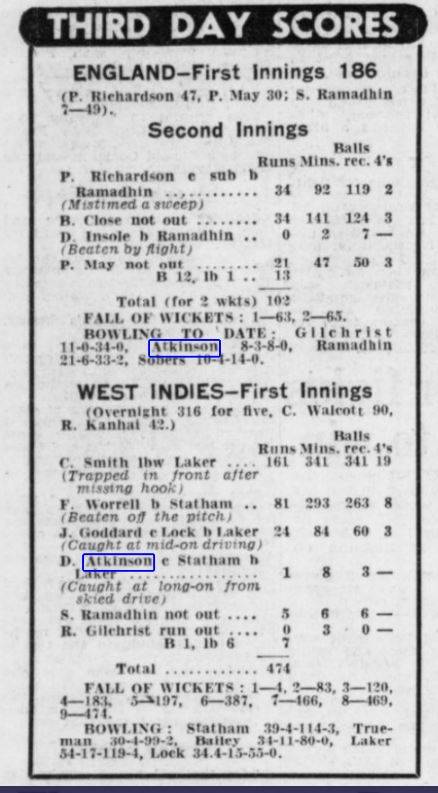

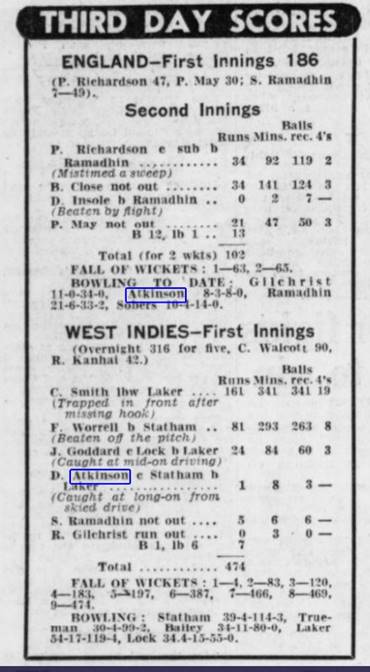

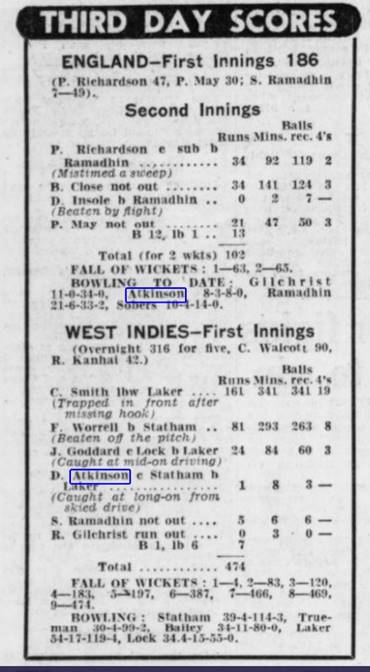

16 April 2025 More on

1957 I mentioned in February the

discovery of some Balls Faced figures for the 1957 England/West Indies

series, found in the Daily Express newspaper. Previously, I had

calculated balls faced figures by re-scoring surviving scorebooks. I have now

tabulated these and compared them to the Express

figures (where available – not all innings were covered) at the link. The comparison

was disconcerting in places, in that there were many differences between the

two data sets. In my original analysis, I had already flagged the fact that

anomalies, even provable errors, had cropped up in some of the scores. This

was not uncommon in scores from this era. Additional uncertainty was created

because byes and leg byes were not marked in the scores; I had to estimate

their position in a way that preserved the batsmen’s runs scored and sequence

of scoring strokes. As a result, balls faced for most large innings contained

uncertainties. If Cowdrey faced

613 balls, then his century came off 527 balls; I previously had 535. The 527

is still the slowest known Test century of all time, although Nazar Mohammad may have exceeded this at Lucknow in

1952-53 (no published figures for Balls faced, but Nazar batted 174 overs to

reach 100, to Cowdrey’s 166). An additional

problem with this innings is the difference in balls faced by the openers.

The rescore gives Peter Richardson 100 balls but the Express says 119,

a wide gap. Once again there are identifiable errors in the score, so maybe

we should accept the Express numbers. But note that the 119 balls

would require about 62 % of the strike to Brian Close’s 38 %, possible but

rather unusual for a 32-over partnership. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have been alerted to a problem with

ball-by-ball files that were posted recently in the online database, wherein

the over-by-over bowler figures could be seriously wrong with respect to runs

conceded. Other columns did not exhibit any problems, so the actual

ball-by-ball data were correct apart from those runs conceded. The problem

cropped up especially in Tests from October 2010 to November 2011. These have

all been fixed now. ******** I was watching the European Club championships,

for a laugh. One team need 65 off the last 17 balls and got them with a ball

to spare. One batsman reached 47 off 10 balls but was out next ball trying to

reach his 50. ******** At Bulawayo in January, Sean Williams was given

not out caught behind, but then walked (there was no

DRS in that Test). I wonder if there are any other examples in recent times.

I recall that Ravi Ashwin once walked when there was no appeal. ******** One thing that has become clear in the DRS era is

that batsmen frequently do not have a clue whether they are out or not, and

even if certain about being not out they can be wrong. There are more than

120 cases of batsmen going to DRS after being given out caught behind, when

in fact they had hit the ball. Many of them were probably hoping for some

glitch in the DRS, but there must also be many who were just kidding

themselves that they hadn't hit the ball. Likewise there must be cases of batsmen who think they

hit the ball but didn't. Lara may be one of them. Mitchell Marsh appeared to

walk before the umpire's decision, after missing the ball at Adelaide in

December. |

4 April 2025 Back pain is making life a bit of a misery at the moment; I am slowing down. Anyway, here is some

broader data on dropped catches over the last eight years on a team basis,

drawn from Cricinfo’s ball-by-ball texts. I won’t say much about it; make of it what you will.

There is a broad but slight improvement trend in this century, but results

for individuals years for particular

countries can vary a lot. I am a bit mystified by Pakistan’s good

showing in some years. My general impression has been that Pakistan is a weak

catching team, but they seem to have spells of very good results. I mentioned

recently that I could not find any dropped catches at all in a recent Test

involving Pakistan at Multan. That Test was in 2025 and is not included in

the data here.

Using the Cricinfo bbb texts, I have analysed more than

one thousand Tests for dropped catches going back to 2001. (I started this

process around 2008 but went back and did some earlier Tests from 2001 on,

and a few from 1999 and 2000). I have also obtained drop catch data for

almost 400 earlier Tests, the majority involving Australia or England. The

total represents drop catch data for about 55 per cent of all Tests. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A small adjustment; at

Bridgetown in 1983, West Indies target of just one run was reached with a no

ball bowled by Kirmani. While Kirmani was (correctly) recorded as bowling 0.1

overs, it can be confirmed that he bowled two deliveries to Greenidge

(source, Barbados Advocate) including the no ball from "a run up

longer than Michael Holding's". Greenidge did not hit either delivery. https://www.sportstats.com.au/zArchive/1980s/1982WI/1982WI4.pdf ******** |

12 March 2025 Four Wickets in Five Balls: a Discovery Coming back from an Antarctic cruise, I found that

the ACS Journal has published a little article of mine, on the discovery of a

previously unknown case of four wickets in five balls in a Test match, taken

by Imran Khan in a Test match at Sialkot in 1985. The discovery was made by

my Pakistan contact Shahzad Khan, hence he is listed as lead author. I have rendered the score supplied by Shahzad into

ball-by-ball form, as best as I was able. Although the score, like many from

the subcontinent in the 1980s, contained anomalies and unexplained

inconsistencies, the section containing Imran’s feat was not in doubt. https://www.sportstats.com.au/zArchive/1980s/1985PL/1985PL2bbb1.pdf https://www.sportstats.com.au/zArchive/1980s/1985PL/1985PL2.pdf ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The England Women managed to drop seven catches

in one day on the way to being clobbered by an innings in the Test at the

MCG. I can find only one men’s Test team that can top that – Pakistan v

England at Faisalabad on 22nd Nov 2005, dropping eight catches and

taking only two on the third day of the Test. ******** |

2 February 2025 Early Reports of Balls Faced in

Tests

I wondered if

this reporting might have been related to Bill Ferguson coming out of

retirement to score this series. However, the Express maintained this

style right through the series including the 5th Test, even after Ferguson

suffered a terrible misfortune after the 4th Test. I haven’t seen a full

description of what happened to Fergie, but it appears that he had a bad fall

at a hotel in August, was in hospital for quite some time, then died on 22nd September shortly after

being discharged from hospital. He did not score the final Test of the series

in August. This was the

first year of such detailed reporting in the Express. In 1956, there

was a column for minutes batted but not Balls Faced. After 1957, the BF

reporting continued up to 1961 for home Tests. They gave up on it for the

1962 Tests, and it is a shame that it didn’t catch on elsewhere. It has created a

bit of a problem; the BF data found so far is sometimes difficult to reconcile fully with my

own re-scoring of the traditional scoresheets preserved from this series. I

will have to study this more at some stage. The Daily

Express has been a paper that has mostly been out of reach in Australia

in the past. The extended British Newspaper Archive (subscription required)

has been progressively adding more years of this most useful paper to its

online service. ******** Compiling some more dropped catch reports, I found

up to seven missed chances in a single innings of 234 by Rahmat Shah of

Afghanistan against Zimbabwe at Bulawayo last month. This would be a

modern-day record, comparable to the all-time high set by Bonnor in 1883.

However, some are ambiguous and opinions may vary on which if any should be

excluded. Here are the Cricinfo descriptions... 10.4^2&Nyamhuri to Rahmat, 2 runs,dropped by Myers at the gully region! Short of

a length ball angling away with extra

bounce, slices it straight to the gully fielder, tires to reverse cup it and goes

through the hands of Myers!,, 18.4^•&Muzarabani to Rahmat, no run,Back of a length ball on the fifth stump line,

punches off the back foot, thick

outside edge to the gully fielder, dives to his left-side and grassed it! Myers is the

fielder there, dropped his second

today, both chances were extremely difficult though.,, 28.5^4&Williams to Rahmat, FOUR runs,dropped again! Quicker length ball cuts it

square and thick outside edge past

the first slip fielder, similar to the one

Ervine dropped earlier, shoulder

height and slow reaction from the fielder,, 37.2^3&Williams to Rahmat, 3 runs,chance! Full ball just outside off. Turning

away and Rahmat attempts a drive.

Takes the outside edge and goes past the diving first slip fielder. Down to deep third for three runs

with Mavuta's slide stopping the boundary,, 79.6^1&Williams to Rahmat, 1 run,dropped! Last ball before the second new ball

gets available! Full ball on middle,

Rahmat comes down the track, lifts it down

the V, and Nyamhuri at long-on has misjudged

it! He runs in, then tries to

backtrack, and all he can get is a fingertip! Williams looks

disappointed and Shahidi survives,, 92.5^•&Muzarabani to Rahmat, no run,Muzarabani dropped a sitter! Back of a length

ball on the leg stump, plays the leg

glance shot early and finds the leading edge, hits it straight back to the bowler, easy

pickings for the bowler and Muzarabani fumbles it!,, 116.4^•&Williams to Rahmat, no run,Another dropped catch? Back of a length ball

turning away on the off stump, plays

the square cut late, extra bounce and might have outside edged back to the keeper, Gumbie

failed to grab the ball. The reaction

from Ervine at the first slip position explains everything.,, AND here are the

Cricbuzz descriptions. There are certainly some

differences... 10.4 Newman Nyamhuri

to Rahmat, 2 runs, dropped! Back of a length outside off, Rahmat cuts and doesn't bother to

keep it down. Goes quickly to gully and

Dion Myers fails to hold onto it. Tries to reverse-cup and the ball

bursts through his palms 18.4 Muzarabani to

Rahmat, no run, back of length and wide, Rahmat pushes at it away from the body and the ball takes a

thick edge. Dies down onto the gully

fielder who was leaping forward. Just short 28.5 Williams to Rahmat, FOUR, dropped! short

on length onto off, Rahmat tries to

cut and gets an edge that flies to the left of first slip. Whizzes past him before he could react and runs away

for four 37.2 Williams to Rahmat, 3 runs, slower

through the air, Rahmat goes for the drive and the outside edge beats a diving Ervine to his

right at first slip 79.6 Williams to Rahmat, 1 run, dropped! A

miscued lofted drive from Rahmat

after he shimmies down the track. Nyamhuri

backpedals from deep-ish mid-on and fails to hold onto it as he tries to

catch it overhead. Another reprieve

for Rahmat! Williams won't be happy with that 92.5 Muzarabani to

Rahmat, no run, dropped! Back of length and gets some extra bounce onto off stump, Rahmat tried to

clip it leg side but gets a leading

edge that lobs back to the bowler. A simple return catch put down by

the bowler. Rahmat Shah gets two

lives in this over! 116.4 Williams to Rahmat, no run, short and

extra bounce outside off, goes over

the attempted cut I concluded that the 37.2 “3 runs,chance!” incident was not really a dropped

catch. (Some reporters don’t use ‘chance’ to mean a dropped catch.) That leaves us

with six dropped catches in Rahmat’s innings. A couple of little extras on dropped catches... -

When Harry Brook scored 171 at Christchurch, he was missed five times.

This equals an England 'record' (again, very much a 'where known' record) of

WG Grace (170) in 1886. As often happens, there is some ambiguity about

Brooks' tally: one of the misses was called leg bye by the umpire,

but was clearly off the bat on replay. If the keeper had made the

catch, a review would have overturned the leg bye call, so it should stand as

a dropped catch. -

I could not find a single dropped catch in the first Test between West

Indies and Pakistan at Multan a few weeks ago. A contact of mine who also

follows these things (Garry Morgan) concurs. In the last 20-odd years I think

that there are only a couple of other completed Tests where I could not find

any misses. I have updated a list of the most fumble-favoured

innings in Tests. Naturally, there could be others yet to be recognised… Batsmen dropped most times in a Test

innings (where known)

UPDATE: Trevor Bailey was reportedly dropped five

times in making 82 against West Indies at Lord’s in 1957. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the start of the Border-Gavaskar Trophy

series, Virat Kohli needed 49 runs of Nathan Lyon's bowling to set a new

head-to-head record. However, he managed only 44 runs off Lyon in 5

Tests, taking him to 573 runs, short of the 577 by Steve Smith off Broad.

Kohli did manage to top Pujara's take off Lyon of 571 runs. Most would have backed Kohli to take this record,

but a combination of Kohli's indifferent form, and Lyon hardly being given a

proper bowl, denied him. It is conceivable that they will play one another

again. ******** A few little notes from a day at the cricket... There was a 'double overthrow', although only 3 runs

were scored. I know Allan Knott once got a seven this way, but does anyone

know of other instances? There were no

advertising logos painted on the (hallowed) turf, just one word

"Melbourne" at the east end. I wonder if this was a change of

policy, or not enough sponsorship. I saw Mike Walsh's name as one of the official

scorers. Mike first scored a Test match at the MCG in 1980-81. Eden Gardens’ record for biggest whole-Test crowd

still stands, although this match was the biggest accurately-counted

match. ******** As far as long-serving scorers go, Dr Murray

Power has been scoring for Ireland since 1976, although full Test matches

only started for Ireland much more recently. Apparently the MCG Test was Mike Walsh’s 101st

Test as scorer. Amazingly he is only halfway to Bill Ferguson’s tally. I saw

an inaccurate number given online for Fergie and took a closer look. Fergie

himself claimed that he scored 204 Tests. However, this includes the final

test of 1930-31, whereas the surviving score for this Test includes a note

that Fergie was ill and there was a stand-in scorer. ******** In the 1982-83 Ashes, Ian Botham either batted or

bowled on all 25 days of the five-Test series. Wally Hammond batted or bowled on 30 days of the

1928-29 series, but there were 33 days play in that series (Timeless Tests). There were only 21 days in the 2009 Ashes, but

Stuart Broad batted or bowled on all of them. Also on 21, VS Hazare in Aus in

1947-48, KR Miller in 1950-51 Ashes, and NAT Adcock SA v Eng 1960. Haven't checked these numbers thoroughly. Data is

from bbb files only. ******** |

13 January 2025 Sobers – Separating his Bowling

Styles I have been asked a few times over the years about

Garry Sobers’ variety of bowling styles and what contribution each style made

to his statistics – has anyone compiled any data on this question? I haven’t

seen any, so I took a little time and did some research on this. Unfortunately the surviving scorebooks provide almost no relevant

information, with no specification of bowling styles at different times. So I turned to detailed newspaper reports and/or film

highlights where available – ten series in all. The selected series extended

from 1959-60 to 1973, covering 44 Tests in all, more than half of Sobers’

Tests in this period. In a few of the Tests, Sobers took no wickets. In

the Tests where he took wickets, I was able to distinguish between pace and

spin for all his wickets, almost 150 of his 235 career wickets. Results look

like so… Garfield

Sobers – Wickets by Bowling Type (Selected Series)

(Unfortunately, in most cases I wasn’t always able

to glean enough info to distinguish between Sobers’ finger-spin and

wrist-spin styles. Sobers said in his autobiography that he stopped bowling

wrist spin after 1966 due to shoulder problems.) While this is not necessarily a random sampling of

Sobers’ Tests in this period, it is quite a large sample. There were about 15 Tests out of the 44 in which he

took wickets with both pace and spin within the same match. There is definitely a

historical pattern. While I didn’t do detailed research prior to 1960, what I

did see suggested that all Sobers’ early wickets were taken with spin bowling

– finger-spin I think (although some reports talk of him bowling “leg breaks”

which I take to mean left arm orthodox). Sobers had been selected initially

as a spin bowler, but within a few years he was setting world records as a

batsman, while his bowling efforts were moderate at best. In 1960-61, he

introduced his pace bowling style, probably because the team touring

Australia was already stronger in spin than pace. In 1961-62 at home, wickets

were more spin friendly and he took most of his wickets accordingly. For a number of years, he mixed his bowling styles with

considerable success. In later Tests, after 1968-69 in Australia, the

table shows that Sobers bowled less and less spin.

This was also evident in detailed film highlights of the World XI matches in

1971-72, where all the bowling that I could see was pace bowling. Here is a second table summarising all of Sobers’

Test wickets. Some estimates are necessary but I

think the final result would be reasonably robust.

I would stress that I have no information on the

number of overs or runs conceded using the different styles in the above

tables. Note that Sobers’ bowling average in his spin-only stage up to 1960

was a rather indifferent 45.0 (32 Tests, 40 wickets). His bowling average in

his later pace-only Tests from 1969 was 30.9 (20 Tests, 53 wickets). I note that some reporters describe his pace bowling

as “medium pace” and others say “fast-medium”. I don’t know if the

distinctions are meaningful; others may know more about this. ********* Sam Konstas, in the MCG Test against India, scored

his first 50 runs in Test cricket just 66 minutes into his first Test match,

facing 52 balls. Probably the fastest for any player: PP Shaw took about 75

minutes for India in 2018, although that time is only an estimate. Shaw

scored 75 before lunch, the most (in a strictly 2-hour session) by any

debutant on the first day. LJ Tancred scored 87 before lunch on debut in

1902, in a slightly extended session. Konstas’s 60

runs was also just shy of Rick Darling’s 61 before lunch on debut in 1978. ******** Fewest Balls Faced for an Innings over

60, All Tests

Complete innings only. Others have reached 60 in

fewer balls, but they continued batting. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I have mentioned players with the most run out

credits in the past (still led by Jack Hobbs with 19). But what of the

players with fewest credits? The only players with more than 100 Tests and no

run out credits at all are Ross Taylor (112 Tests) and Matthew Hayden (103) Mark Waugh (128), VVS Laxman (134) and

Inzamam-ul-Haq (120) had only one run out credit each. Joe Root in 150 Tests has 3 run out credits.

However, two of them are ‘secondary’ in that he is the second fielder listed.

Shane Warne in his 145 Tests had the same run out stats as Root (1 primary 2

secondary) It is apparent that run outs by slip fielders are

rare. ******** Something a little different. After some

controversy over Mohammad Siraj’s penchant for the ‘celebrappeal’

(wildly celebrating an lbw or caught behind without actually

consulting the umpire) I searched some Cricinfo ball-by-ball texts for

that word. This was a very quick search not using any other

terms, so it probably misses some. Results... In 170 recent Tests, there were 38 references to

"celebrappeal". 17 of the 38 went to

review. Stuart Broad was the bowler 11 times, Siraj 5. No

one else more than 2. One by Bangladesh was described as "Broad-esque", another "a Broad-level celebrappeal" Of Siraj's five, none were out. Two were reviewed

but not out, one would have been out but India

decided not to review. Of Broad's 11, only two were given out by the

umpire, one of which was overturned on review. One other was given not out, but overturned on a bowling review. In another of

Broad's celebrappeals a run out occurred while

Broad was doing his dance. I should add that 18 of the 38 were actually out, so Broad's and Siraj's success rates with

their celebrappeals were particularly low. Later: when I extended the search to look at some

earlier Tests and found another 12 references to Broad's celebrappeals

(6 of them were OUT). The first occurrence of the word seems to be 2015 -

Broad again (Durban 2015). That reference says "Broad's celebrappeal was justified this time" suggesting

that it was well-known behaviour before that. The word may well have been

invented in Broad’s honour. ******** Another rarity: In the Adelaide Test against

India, Scott Boland took a wicket with his first ball in the second innings,

after having a catch taken off a no ball with his first delivery of the first

innings. I can only find two cases of a bowler taking a

wicket with his first ball in both innings - Akshar Patel at Ahmedababd 2021 and Zaheer Khan at Mirpur 2007.

Suggestions welcome. In Zaheer’s case, it was the very first ball of both

innings. ******** |

21 December 2024 The online database is now complete up to and

including the 2010-11 season. I don’t know how much further I will take it: certainly up to 2012, but beyond that, sources independent

of Cricinfo/Cricket Archive become progressively harder to find, and so for

many Tests I am not adding much to sources already available. I would like to stress that I am happy to supply

ball-by-ball Test data to amateur researchers (in line-per-ball Excel

format), within reason but free of charge. ‘Reason’ being single series or

season, usually, but ask if you would like more. I am also happy to share series from my ODI

ball-by-ball data, which is not online. I don’t know if or when any of this

will make it to the web. I currently have bbb records for about 800 ODIs from

the 20th Century. These data are not evenly distributed;

Australian coverage is extensive, matches from the subcontinent far less so.

I am hopeful of obtaining more in the future. ******* Stuck in the 90s Following up an enquiry, I dipped into the data to

find out which individual innings involved the most balls faced in the 90s.

The data that I have features the following Most Balls Faced in the 90s

Note Washbrook turning up 1st and 3rd,

and from consecutive Tests! Washbrook’s 114 off 455

balls is one of the strangest centuries; he also spent 67 balls stuck on his

final score of 114, before being dismissed by Ramadhin

in his 10th consecutive maiden over. Batting like that seems

simply weird today. There seems to have been be a

‘culture’ among many batsmen in the 1950s and 60s that accurate finger-spin

bowling could not be hit. Note also that for Washbrook (and for a number of the other innings in the table) the number of

balls is plus or minus 2 or 3 due to unmarked leg byes in the scores. Most Balls Faced on 99

Most balls faced on 99 by a batsman who was out for

99 is 17 balls by JG Wright v Eng Christchurch 1991-92. In actual time in the 90s, the most may be ~98

minutes by Saqlain Mushtaq (above). Michael Vaughan’s effort took 87 minutes. There are probably some cases to be found in Tests

that haven’t made it into the ball-by-ball database. ‘Slow-scoring’

records like this tend to be more common in the past, when more Tests are

missing. At the other end of the scale, I had thought for a

long time that no centurion had ever spent only one ball in the 90s. However,

last year Ben Stokes managed it at Lord’s against Australia, going from 88 to

100 with sixes off consecutive balls. He went from 78 to 100 off four legal

balls plus a wide. If anyone can think of other possibilities not

covered, let me know. I checked Jaisimha’s 99 in 504 minutes

but I don’t think it would feature. When Nazar Mohammad took almost nine

hours to reach 100 in 1952, he actually sped up a

bit in the 90s. ******** There is no precedent for a #10 and #11 (Jasprit and

Akash at the ’Gabba) batsmen needing 33 or more runs to save the follow-on, and actually getting

them. The most by any team needing to save the follow-on

with the 10th wicket is 40 by Bangladesh v Sri Lanka in 2009. The batsmen

were #9 and #11. (I only looked at Tests with 200-run follow-on.) ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the Test Match Database, quite a few

discrepancies have been found in secondary stats (such as minutes batted)

between the main scorecards on the one hand and the table of half-centuries

on the other. Most of these problems have come from revisions to the main

scorecards that I have neglected to transfer through to the 50+ files. For

early Tests especially, these problems often derive from uncertainties and

conflicts in the reports that match scorecards are based on. I have now been through all the anomalies and I have corrected as many of the conflicts as

possible. For example, in the very first Test, I have settled on 210 minutes

for an innings of 63 by H Jupp, as per the main scorecard, previously given

as 191 minutes in the 50+ file. Most corrections are smaller than this. ******** My blog has now passed the 20-year mark. The

first entry was on 6 November 2004. The early

entries are mostly copies of the short columns I wrote for The Age newspaper

at the time. I haven't changed the format of the blog much in 20 years, due

to lack of computer skills. Now very old-fashioned. So be it. ******** In the India A match in Melbourne the other day,

the first four balls of Australia A second innings were faced by four

different batsmen. It went 1,W,W,0 ******** |

29 November 2024 Nathan McSweeney, making his Test debut against

India in the Perth Test, took a catch after just 13 balls were bowled in the

match. Sounds rare, but it turns out to be a bit more common than I thought.

Here are some other names for catches on Test debut in the first over of the

match… HJ Tayfield 0.2 RG Hart 0.3 IM Chappell 0.3 PJP Burge 0.4 MRJ Veletta 0.4 IG Butler 0.5 While ball-by-ball data is incomplete for many

Tests, I have reason to believe that the above list is complete. I had a memory of Chris Sabburg, who never played

first-class cricket, taking a catch (off Kevin Pietersen) on his first ball

as fielding substitute at the ’Gabba in 2013. However, according to an

interview with Sabburg on YouTube, he had been a

sub for a couple of overs earlier in the day, so that disqualifies him; he

came on a second time and took the catch second ball. In innings two of a Test, Allen Lissette in 1955 and

Pragyan Ojha in 2009 took a catch off their first ball when fielding on

debut. Both had batted earlier in the match. ******** Here is an example of the pitfalls of producing a

table of records based on very incomplete information. When Marnus

Labuschagne was out for 2 off 52 balls in Perth, the Fox Sports website (but

not the TV coverage) put up a supposed list of slowest Test innings by

Australian batsmen…

Unfortunately this list is based on dodgy information. When I

generated a list from my own database, using the same qualification of 50

balls minimum, I got the following…

So there are significant additions. There is also an error

in the TV list – Peter Taylor never scored 4 off 66 balls. The online

scorecards do show this for St John’s in 1991, but Taylor actually

scored 4 off 41 balls, not 66. One reason for this error is that slow-scoring

records were often set long ago, and Cricinfo/Cricket Archive lack the needed

detail for early Tests. By contrast, fast-scoring records are often quite recent so they do better with that category. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It was a long wait, but the 100th

score of 250 or more in Tests has finally arrived thanks to

Joe Root. Root’s 262 came 106 Tests after the previous score of 250 (252 by

Tom Latham at Christchurch in 2022). This was equal to the longest pause, in

terms of Tests played, between 250s in history: there was also a gap of 106

Tests in the 1980s. Root clocked up the 100th in Multan

just half an hour in playing time – 9 overs – ahead of Harry Brook, who

went on to 317, which I supposed was the shortest gap between 250s except

that the case of Jayawardene and Sangakkara reaching 250 against South Africa

in 2006 was extremely similar. Prior to the 106-Test gap, there had been a

53-Test gap going back to Kane Williamson’s 251 in 2020. This represents

quite a dearth of giant scores in this decade, maybe an effect of ‘Bazball’. Modern batsmen are so prone to hitting the ball

in the air nowadays that it is perhaps not surprising that giant scores have

become so rare. Having said that, it is interesting that Root and Brook hit

only 3 sixes in their combined 579 runs. There were six 250s in the space of 25 Tests in

1957-58. ********* At Chittagong in March, Prabath Jayasuriya was dropped

by three Bangladeshi slips fielders off the same ball. Jayauriya

was on 6 when he edged a ball off Khaled Ahmed; Shanto

at 1st slip missed the chance but it then deflected to Dipu at 2nd

and on to Zakir at 3rd, but none of them could hang on. ******** |

4 November 2024 Why Eleven? There was an interesting question on a ACS chat site a little while back: what is the origin of

having eleven players in a cricket team? In truth the answer is lost in the mists of time.

The earliest surviving scorecards, from 1744, have teams of eleven, but

earlier descriptions of the game generally lack the detail to help with the

question of origins. The 1727 ‘Goodwood’ rules for a cricket match in Sussex

describes teams of twelve, which complicates things, but it is understood

(not sure how) that eleven was the standard. Someone asked the much-vaunted AI, which came up

with a completely useless answer. The most satisfying answer offered was from Eric

Parker’s History of Cricket, published around 1950. He pointed out how

the numbers 11 and 22 crop up (so to speak) regularly in traditional farming

practices in England. There are 22 yards in one chain, a common farm

measurement; farms possessed a literal chain created for the purpose. Easy to

measure out a cricket pitch. There were 10 chains to a furlong (a “long

furrow” = 220 yards) and eight furlongs to a mile. An area one chain by one

furlong was an acre, being the area that one worker

could plough in one day with a team of oxen. The original stumps (two of them in underarm days)

were 22 inches high placed five and a half inches apart; the ball was five

and a half ounces. I like the connection with the number 22. Beyond

that we don’t have a terribly clear idea when the idea of applying it to

cricket matches arose. ******** It appears that the protocol for measuring minutes

batted has changed, at least as far as online scores go. Drinks breaks are no

longer included in batting times. This represents a break with traditional

practice. While the change has some logic, that break makes historical

comparisons a little harder. Here is a comparison of a recent innings from

Pakistan. The CA/CI (Cricket Archive/Cricinfo) times are on the left and

exclude drinks breaks. Source BB is a score that includes drinks breaks, and

Source C is similar.

There is potential for confusion if the protocols

get mixed, such as when one protocol is used for the whole innings but

another for milestones (50s, 100s etc) from different source. The differences

in the above data, while sometimes small, appear to go beyond exclusion of

drinks breaks. ******** The Draw Drought One effect of the escalation of big hitting and high

strike rates in Tests has been the near-disappearance

of drawn Tests. The trend has been particularly strong in the last year. In

the last 50-odd Tests, there has been only one Test that was drawn after play

on Day 5 (and one other where Day 5 was rained out). That Test, West Indies v

South Africa at Port-of Spain in August, had four full sessions lost to bad

weather, and other sessions shortened. This was brought home when draws seemed to be a

foregone conclusion in two recent Tests; there seemed to be no chance of

results after Day 3 at Kanpur (India v Bangladesh, where almost 3 days were

lost to weather) and Multan (Pakistan v England, with first innings of 566

and 823), yet both Tests were completed with time to spare. The lack of dull draws is surely welcome, yet with

that comes the disappearance of exciting draws. In the last 100 Tests, there

has been only one that I would class as a draw with a close finish: at

Karachi in 2023 Pakistan (449 & 277/5) v New Zealand (408 & 304/9).

Close Tests haven’t disappeared entirely – there was New Zealand winning off

the last ball at Christchurch in 2023 against Sri Lanka – but hopes for

forcing a draw against the odds are rare now. Nevertheless

the preponderance of result Tests means that such Tests that have close

finishes still occur fairly regularly. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lawrie Colliver has provided a re-score of an ODI

that Australia played in Pakistan in 1988, scored from a newly-discovered

video. It was the only ODI that Australia played on that tour, the others

being cancelled due to floods and rioting in the aftermath of the

assassination of President Zia. apiece – but Pakistan was declared the winner on

account of losing fewer wickets (7 to 8). As far as I know, it is one of only

two tied ODIs decided by this method. It appeared especially odd because,

with the scores tied, Pakistan made no attempt to score from the last five

balls, bowled by Dodemaide . Presumably they knew that they were ‘ahead’, but it

almost came unstuck when a wicket fell off the second last ball. Abdul Qadir

faced the last ball and padded it away. A wicket here would have tied the game

in wickets as well as runs. Lawrie’s notes describe it as “plumb” but it was given not out, and so Pakistan won. ******** India had a remarkable win in the recent Kanpur

Test, coming after more than two days were washed out. It was the first time

that a team has started its first innings on the fourth day and won, with the

peculiar exception of the Cronje 'Leather Jacket' Test. The fourth day also featured the most wickets on

a day with over 400 runs. 437 runs, 18 wickets (85 overs), previously 447/17

(91.4 overs) at The Oval 2013, and 414/17 at Lord's 1931. ******** |

October 2024 A Brief History of Rest Days A recent Test in Sri Lanka had a ‘Rest’ day – actually a pause for a national election. Like the handful

of Tests in this Century that had such pauses, there were special

circumstance involved. The ToSh group had a

little discussion about this, and it got me looking into the history of Rest

Days. I was surprised by some of the observations. The insertion of days off into Test matches,

specifically as rest days, dates only from the 1950s. Prior to that all ‘rest

days’ were literal days of rest, i.e., Sundays, with the occasional pause

also on Christmas Day. For a long time, playing cricket on a Sunday was

severely frowned upon, or even illegal, in Christian countries. Some of the

earliest written records of cricket in the 17th Century are court

records of people fined for playing cricket on the Sabbath. In England, there were no rest days of any kind

prior to 1920. All Tests were three days, commencing early- or mid-week,

aligned with County matches. In Australia, Tests were longer and often

encompassed the weekend, but days off were always on a Sunday, even if the

match started on a Saturday. There is one Test that shows that the idea of

simply granting players a day off did not apply in those days: the first Test

of 1897-98 at the SCG started on a Monday and went for five days without a

break. In 1921, some Tests in England started to straddle

the weekend and the Sunday prohibition applied. It was similar in South

Africa, where a Test in 1922-23 actually had two

consecutive days off, a Sunday and Christmas Day on the Monday. The epic

Durban Test of 1939 had two Sundays in addition to the ten scheduled days. The first Tests with Sunday play occurred during

England’s first tour of India in 1933-34. When West Indies toured India in

1948-49, there was play on Sundays and the five-day Tests had no rest days.

The idea of regular rest days seems to have emerged in the 1951-52 England

tour of India, where there was play on Sundays but a day off after Day 3 of

each Test. Rest days soon became the norm in the five-day and

six-day Tests in Australia and England, but invariably these remained on a

Sunday for many years. The West Indies had the same approach; there were also

a couple of Tests which had two rest days because they occurred over Easter,

pausing for Good Friday and Easter Sunday. The last of these was in 1965

(Georgetown). One of the oddest cases was Karachi 1956. There was

a rest after Day 3 (Sunday); then on Monday (Day 4) Pakistan dominated and

were set 69 to win. Incredibly they scored only 63 for 1 in 46 overs before stumps, and so had to come back. The next day was another

rest day (a day of mourning for a political figure) and so they waited till

Wednesday to score the needed six runs. Sunday play in Australia was finally introduced in

1968-69 (although not in all Tests). Those Tests with Sunday play had rest

days after Day 2 or 3. England did not have Sunday play until 1981, and even then it was irregular with most rest days coinciding with

Sunday. After 1986-87, rest days in Australia fade from

view, only occurring under special circumstances. New Zealand followed suit.

(The special circumstances were sometimes very odd: the Brisbane Test of

1995-96 was paused for a day so that the broadcaster could show the

Australian Grand Prix.) Rest days in England remained, when scheduled, on

Sundays, before disappearing in the early 1990s. Rest days were dispensed

with in South Africa when that country returned to Test cricket in 1992, but

they continued to be regularly used in the hotter climes of the subcontinent

and West Indies. In a unique occurrence, a Zimbabwe/New Zealand Test in

November 1992 was paused for a day so that an ODI could be played. Not

exactly a rest day! The pressure of tighter schedules was making its

mark, and the last series with normal rest days appears to be New Zealand in

West Indies in 1996. There was a rest day in India’s first Test there the

following year (on Good Friday), but the other two Tests of the series were

so heavily rain-affected that the idea of rest days did not apply. As said earlier, scheduled pauses in Tests since

then have only occurred under special circumstances. A day was taken in a