For sportstats home page, and info in Test

Cricket in Australia 1877-2002, click here

|

|

Z-score’s Cricket Stats Blog The longest-running cricket stats blog on

the Web

|

|

Charles Davis: Statistician of the Year (Association of Cricket

Statisticians and Historians)

|

Alan Davidson

is one of quite a number of bowlers who

took a wicket with their last ball in Test cricket. But Davidson also

took a wicket with his last ball in a non-Test first-class match, and it was

Garfield Sobers out bowled in a Sheffield Shield match. I reckon that such a

double (Test and non-Test f-c) must be very unusual. That final

Test was a few weeks after the Shield match. ******** When

wicketkeeper Ridley Jacobs was injured in mid-over at Antigua in 1999, the bowler,

Jimmy Adams, donned the pads and took over. This meant that he could not

finish the over, so Carl Hooper finished it for him. ********* In the Old

Trafford Test of 1999, every player for New Zealand went into the Test with a

first-class century to his name. ******** The

Australian tour of England in 1884 was so lucrative that each player made 900

pounds clear profit from the tour. This was at a time when £50 per year was a

very good salary and many in the working class could earn less than £10 per

year. The Governor of the Bank of England had an annual salary of £400 in

1880. The tourists

in 1882 – the year of the original Ashes Test – made between 600 and 700

pounds per man. ******** At Chittagong

in 2008, Daniel Vettori had New Zealand’s best

bowling in both innings, top scored with 55 in the first innings and was 3

runs off top score in the second innings (76 to Redmond's 79). ******** When did the concept of four runs for

a boundary begin? My impression is that the idea of a boundary hit began in

the 1860s. WG Grace said that in his earliest years all hits had to be run,

and that around 1860 he once hit a six and a seven, all run, in the first

over of a match. By 1865 boundary hits were scoring

four in Australia. There is an interesting phrase in a report of an 1865

match at the MCG, saying that Ned Gregory's hits to the fence scored

"four, as per agreement". The use of that phrase suggests that it

was a novel idea. I would be interested if readers have

any other information on this question. ******** Most bowlers go from "x99"

to "x(+1)00" wickets in the same match. At about 326 days, Nathan

Lyon took far longer than anyone to go from 399 to 400, previously Chris

Broad with 76 days. Most for other milestones... 99-100 W Rhodes 548 days. 199-200 CS Martin 288 days 299-300 RJ Hadlee 79 days ******** Historically, there are more than 40

cases in Tests of a batsman facing a hat-trick ball as the first ball of his

career, as Alex Carey did in the Gabba Test. At least three were out to their

first ball, thus completing the hat-trick (TA Ward, FT Badcock and WW Wade).

Ward also faced a hat-trick ball as his second ball in Tests and was out

again, completing TJ Matthews’ second hat-trick at Old Trafford in 1912. ******** From 2013 to 2015, several Australian

teams had eight players born in NSW. There are a number of earlier instances.

At Perth in 2002, Australia had 5

from (born in) NSW and one each from Qld, Vic, SA, WA, Tas and Northern

Territory. ******** Since 2017, when India started using

DRS, Virat Kohli has been out LBW 17 times. One of those came via a

successful bowling review. Of the other 16, Kohli reviewed 14 unsuccessfully.

He chose not to review the other two; ironically one of them would have been

given not out (he was on 204 at the time). He has also made two successful

batting reviews, where the initial LBW decision was overturned. The 14:2 batting LBW review ratio is

the worst among batsmen with 10 or more LBW reviews. David Warner is 8:1. ******** Mayank Agarwal’s 150 in the Mumbai

Test against New Zealand is the highest score ever achieved in the face of a

bowler taking all ten wickets (Ajaz Patel 10 for

119) in all first-class cricket. Previously 149 by Les Ames in 1934, when W Jupp took all ten in a county game. ******** Bangladesh lost a Test against

Pakistan in Dhaka even though they did not commence the first innings until

after lunch on the fourth day. This is the latest ever start for a first

innings in a completed Test. ******** |

15 December 2021 The Curious Case of Frank Irving. You don’t often

come across someone like Frank Irving, a man who, despite playing a role in

four Australian cricket tours to England, has virtually disappeared from the

annals of Australian cricket. They were

historic tours too – the first four Test tours by Australian teams, in 1880,

1882, 1884 and 1886. So what role did Irving play? Until recently, no one has

identified names for scorers for these touring teams: it appears that no

official scorers were appointed. But now some detective work by various

people on an ACS (Statisticians) chat page has produced convincing, if

sometimes circumstantial, evidence that Frank Irving was involved in these

tours as a scorer. Irving was a

newspaperman (specifically, a compositor) with an apparent penchant for long

sea voyages; he travelled to England five times in his short life, and can be

placed in England during all four tours. He acted as a reporter on those

tours for the Advertiser in

Adelaide, even though he was and is largely unknown for such work in

Australia. Nor is his name found in connection with scoring in Australia. Yet

it seems that, after faithfully following the teams around in England, he

came to act as scorer in some historic matches, including the original Ashes

Test in 1882. I asked some of

the luminaries of Australian and South Australian cricket history; they were

unfamiliar with Irving. His name does not appear to be mentioned in the 1882

Ashes Tour book by Charles Pardon or Clarence Moody’s 1898 history of South

Australian cricket, and eluded Michael Ronayne in

his detailed tour summaries covering that period. The Trove newspaper archive

does record his name, but only fleeting references have been found so far;

likewise the British Newspaper Archive. Currently it

appears that Irving was not appointed to tour with the team in an official

capacity, and he did not actually sail with any of the teams. He seems to

have settled into the scorer duties rather unofficially. Note that

players George Bonnor and Jack Blackham are the

only others known to have been involved in all four tours. I would like to

add some evidence from my score collection that links two of the tours. I

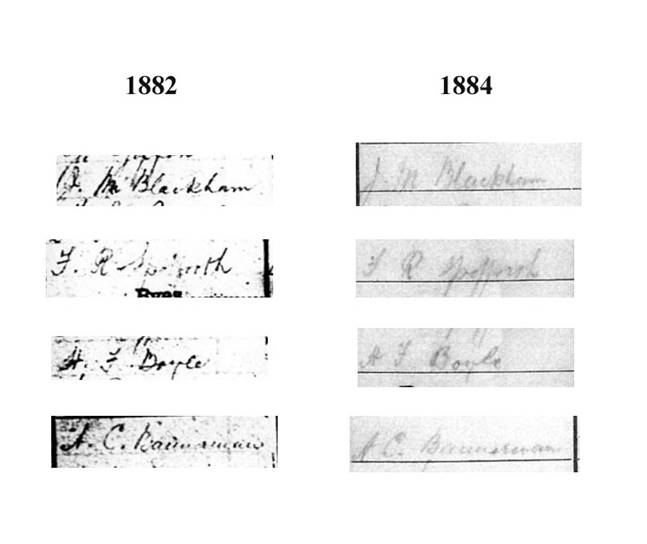

have copies of scores from the 1882 and 1884 Tests from the

respective Australian tour scorebooks, and I am convinced that they were

written by the same person. Examples of the writing are shown below. (The

1880 and 1886 Australian tour books cannot be located; the surviving 1880 score is from

the Surrey CCC and is in a different hand, presumably that of the local

scorer.)

The styles of

numerals are also identical in the two scores. I would add that the method of

recording bowling figures, in both cases, is unusual. In the box for each over,

the four balls are arranged in a square pattern, with the first ball of the

over in the bottom line, like so…

whereas scores made

by others from the period are what I would call more conventional…

This

helps tie together the scorers for 1882 and 1884. The evidence is also clear

that he was scorer in 1886 (see below). The evidence from 1880 is less clear,

but he definitely accompanied the team. While

the Manchester and Oval Test scores from 1884 are complete, it may well be

that Irving did not actually score the second Test at Lord’s. The Lord’s

score is in the same hand as the other Tests but it is incomplete, lacking

detail in the bowling section. It is probably a re-copy made by Irving. There

is another Test in the back of the 1884 scorebook – the first Test of 1884-85

at Adelaide. It was played in December by the 1884 tourists, who were still

together, against the English team that had just arrived in Australia. This

score is not in the same hand as the Tests in England. This suggests rather

strongly that Irving did not accompany the Australian team on their return

voyage. Indeed, passenger manifests show that Irving did not return to

Adelaide until late December, after the Adelaide Test match. The following compiles

information available about Irving, as gathered by various ACS members. The critical

observation that got this investigation going was by Harry Watton when he

picked up the reference to Irving in the December 1902 Cricket magazine. Frank (Francis) Irving Born 1855

Adelaide Joined Advertiser in 1876. 1880 March 1879:

Identified as a printer who was going to England via New Zealand and USA as a

journalist for the Advertiser. His

activities in 1879 are unclear; there is no direct evidence that he was a

scorer in 1880, but he certainly accompanied the team. Returned from

Plymouth to Adelaide departing 2 October 1880. 1882 Listed as a

passenger on the steamer POTOSI sailing from Adelaide bound for London on 13

March 1882, departing three days before the Australian team sailed from

Melbourne. (South Australian Register 14

Mar 1882). Identified as

Australian scorer against Cambridge P&P at Portsmouth (Hampshire Telegraph 19 Aug 1882), a

week before the ‘Ashes’ Test. Frank Irving age

26, listed arriving in Adelaide in Dec 1882 from England on the HAUROTO. This

was not with the team, which had returned via America in November. 1884 In a 1902

interview in Cricket magazine,

Surrey scorer Fred Boyington said that Irving was

his co-scorer in the 1884 Oval Test. A Mr F. Irving, age

~30, is listed as a passenger on the AUSTRAL departing London on 11 Nov 1884,

bound for Adelaide (and on to Melbourne and Sydney). He is the only F. Irving

listed travelling to Adelaide in the years 1883 thru 1885. Newspapers have

him disembarking in Adelaide on Dec 24. 1886 Irving was a

press representative on the tour (as he had been in 1884), the Adelaide Express reporting on 19 April

1886 that Frank Irving is ‘about to visit England [to] represent the Advertiser in connection with the

Australian Eleven’. He is reported in the South

Australian Chronicle of the same day to have made three previous visits

in that capacity (i.e., 1880, 1882 and 1884). A column in the London Evening News of 17 July 1886

refers to ‘[m]y old friend Mr. Frank Irving, the Australian scorer’, and

reports an anecdote of Irving’s from the recent match between Yorkshire and

the Australians on 12-14 July, when the ball had whistled past the scorebox. F. Irving age

~31, occupation compositor, arrived back in Adelaide from England aboard

IBERIA on 7 Jan 1887. 1887: captain of

Advertiser cricket team. 1888 No known

connection with the touring team, or evidence of travel. Leaves for

England again 11 Nov 1889? Died (intestate)

6 May 1890 Carlisle, Cumberland, England, just prior to a planned return to

Australia. He is listed in a ship manifest departing London on 9 May but his

name is crossed out. Irving’s

ancestors and relatives hailed from Dumfries Scotland and the surrounding

area, just over the border a few miles from Carlisle. 21 June 1890: a

short obituary appeared in South

Australian Chronicle (“four trips to England since first journey with the

Australian eleven”) ACS members who gathered the above information

include Harry Watton, Neville Flood and Sreeram Iyer. ******** The Test Match

Database has now reached the 21st Century. It is now well and

truly overlapping with other online ball-by-ball records, but I will continue

with it for now. For some Tests, there is material in my scores (for example,

session scores) that would be rather hard to extract from other online

sources. I don’t know how much further I will take it; who knows what 2022

will bring? ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I came across

a 1982 newspaper article by Bill O’Reilly. He was talking about his early

recollections of cricket broadcasting on television, which he had first seen

in 1938 in England. The match was Middlesex v Australians on 30th

May 1938 (O’Reilly says it was the 28th, but that day was rained

out). This is before the Tests that year, and must represent one of the very

first cricket TV broadcasts. The

television set (super-expensive in those days) was on loan to the hotel where

the Australians were staying. Most curiously, O’Reilly said he was in the

team playing that day, but he had stayed behind in the hotel to deal with

some correspondence! He had expected the team to bat all day, but they

started losing wickets. O’Reilly could see from the broadcast that the pitch

was dodgy, so he hurried down to the ground, and was just in time to bat and

make a duck. ******** I took a look

at the question of a bowler taking a wicket with his last ball of a Test and

first ball of his next, and found only 25 cases (from the database covering

about 85% of Tests). Waqar Younis and Richard Hadlee did it twice. The low

number might seem surprising when you consider that there are well over one

thousand cases of wickets with consecutive balls in general play, but

remember that there is never more than one opportunity per Test match for a

bowler to do take two in two in different Tests (and usually no chance at

all), whereas the same bowler may well have multiple opportunities for two

wickets in two balls during the course of

a Test match. There are no

known cases of three in three across two Tests (a quasi-hat-trick) except for

the extraordinary case of George Lohmann, who took a hat-trick to finish a match

in 1895-96, and then a wicket with his first ball of the next Test, to secure

four wickets in four balls (he made it five in six two balls later). Overall, the

chances of taking a wicket with a hat-trick ball are only 1 in 30, so, given

the low incidence of two in two balls across two matches, it is not

surprising that three in three is so rare. There is an

interesting case of Mervyn Dillon, whose last two balls at Port of Spain in

2002 were a run out and a wicket (in two different overs), followed by a

wicket with his next ball at Bridgetown. Waqar Younis

extended one of his wicket pairs to three wickets in four balls; Rashid Khan

of Afghanistan has done the same, and that was across his first two Test

matches (9 months apart). ******** |

1 November 2021 The Test Match

Database Online has reached a crossover point with the Cricinfo Ball-by-Ball

Archive texts. Beginning with the 1998-99 India v Pakistan series in January

1999, Cricinfo began to archive their bbb logs. I

am fairly certain, from memory, that they were doing some ball-by-ball

descriptions of internationals before that – the earliest record goes back to

the 1996 World Cup final – but for some reason they never preserved them (sad

emoji). If I have checked correctly, the only Test that we have from

Cricinfo, from that period, is a single day from the 1997 India series in

West Indies. The early

Cricinfo texts were typed commentaries and were not designed as rigorous

scores; there are gaps and anomalies. Where necessary (and possible) these

have been adjusted with reference to surviving scores or other published

information. In a few cases, such as the final day of the Asian Test

Championship Final in Dhaka 1999, the gaps and problems are substantial, and

there is no detailed backup. In such cases, I have ‘recreated’ a bbb version that is consistent with surviving scores and

reports. These cases are few and I hope I will be forgiven for doing this for

the sake of completeness. There are

actually seven Tests from the early period that are missing entirely from

Cricinfo, five of them in New Zealand; I have managed to obtain alternative

scores for all of these and so maintain continuity of the ball-by-ball

record. I have also

obtained alternative scores for a significant number of other 21st

Century Tests, but this collection is not comprehensive. Of the first 100

Tests from the ‘Cricinfo era’ starting in 1999, there are The archived

Cricinfo texts gradually improved in detail and reliability, especially after

2002. It would be

wonderful if someone at Cricinfo could unearth some ancient backup tapes from

1997 and 1998 and find some more bbb logs. 1998 is

not so essential as I have all the Test matches from that year already (some

ODIs are missing), but there are considerable gaps in my data for 1997. I

understand that there has been a search of this kind, sadly without success. I am not sure

how far into this new era that my online work will go. But I have been at

this for nine years now and I don’t really know how to stop. ******** The Kolkata Test

of February 1999 at Eden Gardens is one of only seven Tests that Pakistan has

played at that cavernous venue. The match quite possibly attracted the

highest attendance of any Test match; however, the numbers were never

accurately counted. I am told that the ground had 90,462 seats at the time,

so any numbers in excess of that must have been standing room only. The

available numbers are estimates, and it must be said that the estimates vary

widely. I have collected

(with assistance from others) some mentions of crowd numbers from reports at

the time, illustrating the variations in estimates…

Ironically, the

last overs of the match were bowled in a virtually empty stadium, following a

roughhouse clearing out of the final day crowd by police, in response to

serious unrest that suspended play for three hours and 20 minutes. There had

also been serious unrest on Day 4. Even though it

appeared in Wisden, I consider the

estimate of 465,000 to be highly improbable. A figure around 400,000 seems a

reasonable compromise from the conflicting numbers. This number is in the

same ballpark (if I may use the expression) as the estimate of 395,000 for

the Test against Australia at the same Ground in 2001, and the 390,000

estimate from 1981-82. I don’t have figures for Tests at Eden Gardens after

2002, but it has been apparent that Test attendances have been declining in

India, even though interest remains substantial. At the same time, Indian

authorities have been distributing Test matches among a wider range of

smaller venues, and Kolkata has hosted only 12 Tests in 22 years since the

match in question. The largest

accurately measured total attendance for a Test remains the 350,534 over six

days at the MCG back in 1937. The most for a five-day Test is 271,854 for the

MCG Boxing Day Test in 2013-14 (including a ground-high 91,062 on the first

day), and the highest average daily attendance is 81,450 for the equivalent

match in 2006-07, which only lasted three days. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

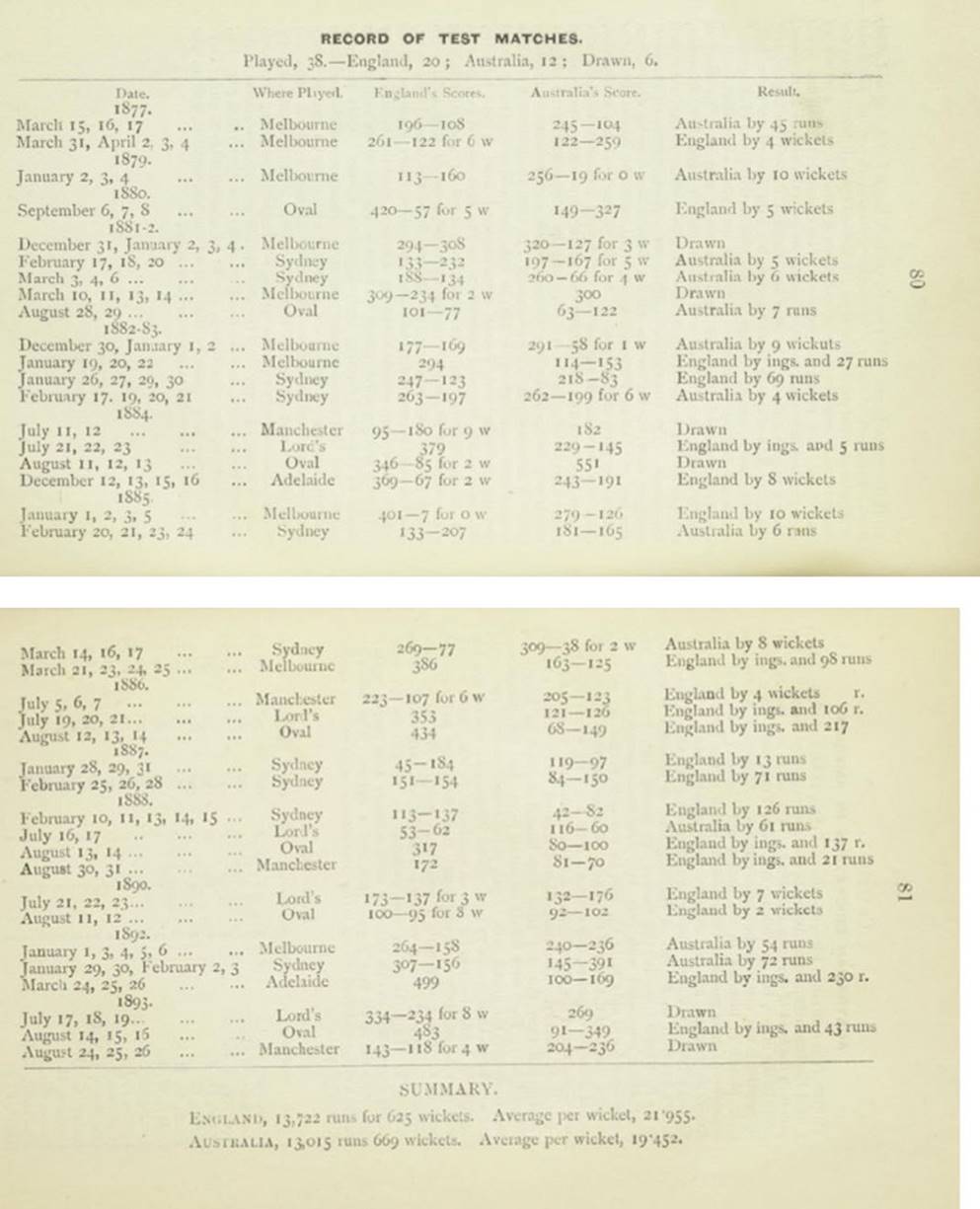

I don’t think I

have discussed before, on this blog, the origins of the early Test match

“canon”, that is, the list of matches regarded as official Tests. It is widely

held that the originator of the list was a South Australian journalist named

Clarence P. Moody. Beyond that, it remains a bit of a mystery how Moody’s

list, drawn up in the 1890s, became accepted as gospel. With limited debate,

and no input from English sources, it has become set in stone, so to speak.

Moody was something of a cricket statistician. He was also a friend of George

Giffen, who may well have suggested the creation of

the list. However, there was never any official imprimatur on Moody’s work. I went looking

for Moody’s original list. Various printed sources and online articles said

that it came from Moody’s 1898 book on South Australian Cricket. I managed to

borrow, from Roger Page, a facsimile copy of this book (originals are rare

and valuable) and was rather surprised to find that it contained no such

list. However, an Introduction to that facsimile edition pointed me to an

earlier (1894) Moody work, Australian

Cricketers 1856-1893-94. Fortunately, the Trove Archive has this book

online, and there can be found the original list, on pages 80 and 81. Clarence Moody’s 1894 list of

Test matches

One noteworthy

aspect is that Moody restricted himself to England v Australia Test matches.

In that respect, the list is indeed identical to the accepted canon, but

there are several other matches, played in South Africa in 1888-89 and

1891-92, that are not included. So how did those Tests get into official

lists? I don’t know but I would like to find out. (I am told that the South

Africa matches were listed as Tests by Ashley-Cooper in a Cricketer Annual in

1930-31, but I don’t know if there are earlier references.) I do know that

there has been plenty of doubt and dispute over the Test status of some matches,

and also some matches that did not make the list but might have. In the case

of 1888-89, even the first-class status can be questioned, since there was no

first-class cricket in South Africa at the time, and a number of the

Englishmen were themselves not first-class cricketers. (A favourite stat: JEP

McMaster played Test cricket, but was out to the only ball he ever faced in

first-class cricket.) In his 1951 collection of Test match scores (The Playfair Book of Test Cricket),

Roy Webber certainly expressed a sceptical view, but he also said that

“little purpose seems to be served by omitting ‘doubtful’ matches”. I agree,

but I think that caveats need always to be expressed when records from those

matches crop up (such as Briggs 15 wickets for 28 at Cape Town, 14 of them

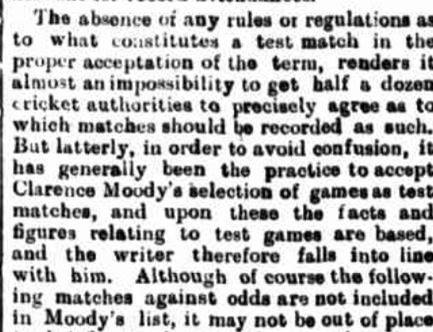

clean bowled). A comment from

the Sydney Sportsman in 1901 seems

pertinent here…

It should be

said that Moody’s list did not require deep scholarship. Once the matches of

1877 are accepted into Test cricket, most of the rest falls into place.

However, the fact that the list came to be used as a reference, in the face

of the disagreements expressed above, makes it important. I won’t go into

the detail of the claims of certain matches for Test status. But here are a

couple of observations: - The touring

English team in 1884-85 did not regard the first two matches, now regarded as

Tests, as authentic. As far as they were concerned there were three Tests in

the series. The canon lists five. - The 1887-88

match was by no means regarded as a proper Test match even in Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald described the

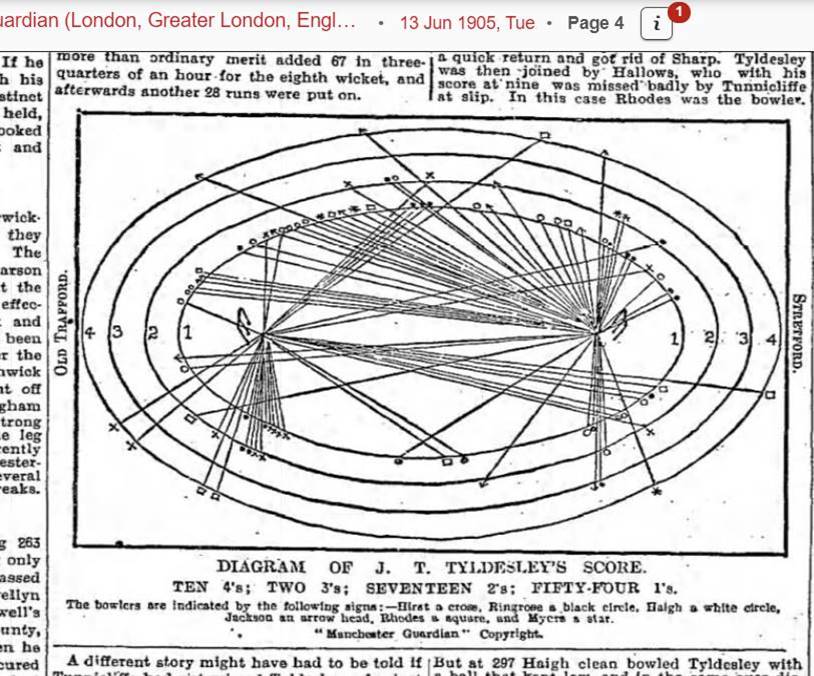

Australians as the "non-representative Australian XI". ******** An Earlier Wagon Wheel I have written

(somewhere) that the first known batting Wagon Wheels were found in Test

match reports in the Daily Express

in 1905. Sreeram has now pushed the date back a little further, finding

similar diagrams in Manchester Guardian

reports for the first Test of that series (innings by Hill and Tyldesley).

Unfortunately, the Guardian reports

do not say how the diagrams were made or by whom, although they do claim

copyright. The Express does suggest

that theirs were drawn up in the newspaper office, based on information

telegraphed or telephoned from the ground. It has been

claimed/reported that Wagon Wheels were invented by Bill Ferguson, who in

1905 was the Australian scorer, making his first of many tours. However, the

diagrams in the British papers are different in style to Ferguson’s, with

concentric circles for each run value. No actual Ferguson-style Wagon Wheels

earlier than 1911 have been sighted. In his

autobiography, Ferguson provides a whole range of examples of his Wagon

Wheels, but he is curiously vague about their development. The earliest

diagram in that book is from 1912 (he didn’t call them “Wagon Wheels” by the

way; I wonder when the term originated). Sreeram has

added further evidence by finding another 1905 Guardian Wagon Wheel, this time from a county match, Lancashire v

Yorkshire in June (Tyldesley 134). It even names the bowlers for each shot.

Ferguson at this

time was elsewhere scoring for the Australian team, so he could not have

contributed to this. I think that it is now fair to say that Ferguson

adopted, rather than invented, the idea of a Wagon Wheel. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the Test

match at The Oval, Rohit Sharma (127) was dismissed by the first ball with

the new ball, after a partnership of 153 with Pujara.

This is the second highest partnership ended by a brand new ball, after a

partnership of 172 between Mark Richardson and Stephen Fleming at Colombo PSS

in 2003.(where known) ******** Something

curious about cricket watching in Sri Lanka…during England’s Test match in

Colombo in 1992-93, the attendance on the Saturday was only about 1,000. On

the same weekend, two interschool matches in Colombo attracted crowds of over

10,000. (source: Sunday Times) ******** Here is a neat

little stat. When West Australian Des Hoare batted for the first time on

debut at Adelaide in 1961, his first ball was from Lance Gibbs, who had just

completed the hat-trick. As far as I

can see, Hoare is the only batsman in Test history whose first ball in Tests

was the first ball after a hat-trick (the double hat-trick ball). Others on

debut have come in after a hat-trick, but it was either the second innings,

or they didn't face the double hat-trick ball. One case was CA Absolom in

1878-79, who came in after Spofforth took a hat-trick, but the hat-trick came

off the last three balls of an over, and Absolom faced a ball in the next

over, before Spofforth bowled again.

******** Longest

sequence of missed chances off a bowler without a catch being taken (data

since 2003)... In 2019, Joe

Root had a sequence of seven chances missed off his bowling, without any

catches being taken, spread over three Tests. Same thing happened to Nathan

Hauritz in 2010, again over multiple Tests. ******** It hadn't

occurred to me until a question on Ask Steven, but I found that never before

had a team, behind on first innings, declared its second innings after lunch

on the 5th day, and won. This is what India did to England at Lord's. ******** The most

threes in a Test career were hit by Steve Waugh (397) and Ricky Ponting

(381). The top six positions are held by Australians who were active (at

least in part) during the 1990s, before the much-lamented ‘shrinking’ of the

grounds and the advent of Super Bats. Mark Taylor hit 354 threes or 14.1% of

his runs; this is the highest percentage of any major batsman. Threes have

always been more common on the larger Australian grounds. The top 13

positions are held by Australian or English batsmen. ****** |

16 September 2021 I have been

working on a list

of “Unusual Dismissals” in Test matches. This is largely

drawn from notes that I have made over the years in my study of Test matches

and scorebooks, rather than specific research. Some of the instances have

been thanks to suggestions by others. The stimulus to

finally put this together was the dismissal of Nauman Ali at Harare earlier

this year, stumped by Chakabva off a wide. As far

as I know, this was unprecedented in Test matches, although it happens from

time to time in limited overs games. Any suggestions

for additions would be welcome. The general criteria include: a dismissal

must have occurred, and there must have been something very unusual about the

dismissal itself, not just the situation (for instance, run out for 99 is not

included unless there was something strange about the dismissal). Also

excluded is where one fielder drops a catch and deflects to another: there

are actually many examples of this in Tests. Bowlers deflecting a shot to

effect a run out is also excluded, unless it was a dropped catch. ******** While checking

through the list of most

overs in a day by individual bowlers, I noticed again the

absence of any modern names. The list is effectively set in stone, and is

dominated by Tests where over rates were high and days lasted six hours. Most

instances came from the 1940s and early 1950s, when some captains, rather

lacking in imagination, would put spin bowlers on and just keep them bowling.

This certainly applied to John Goddard of the West Indies. So I have

prepared a separate list for Tests since 1998. Most Overs in a Day: individual

bowlers since 1998.

Incomplete overs counted as one There are ten

cases of 39 overs. Even in this list, the near absence of instances in the

last ten years is notable, with just one appearance, by Jadeja. There are

only three instances from the last ten years in the Top 30. By contrast,

Muralitharan appears ten times in the Top 30, and even then his Tests before

1998 are not included. There are

worrying signs that over rates are on the way down again. It has become

unusual for teams get through 90 overs in the allotted six hours, often not

even in the allowed extension to 6.5 hours. The great majority of innings in

Tests this year have recorded over rates of 80 balls per hour or less (40 out

of the last 46 innings). In the 1960s, rates of more than 100 balls per hour

were commonplace; in the 1940s and earlier, it was 120 balls per hour or

more. Fielding sides

are mostly to blame, but not entirely. Batsmen nowadays often go through

elaborate preparations and are quite frequently not ready to face when a

bowler is trying to get through an over more quickly than usual. ******** There has been a

general checking and updating of various records in the “Unusual

Records” section. Not everything has been checked, but

those sections that have been checked have been appropriately labelled with a

date. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A scoring

curiosity: in the second Test between Zimbabwe and New Zealand at Harare in

1997-98, it appears that when no balls were scored from, an extra run was

added (for example, a no ball hit for four added five runs to the total).

This was not the established protocol at the time: the practice came into

general use about a year later. There were no instances in the first Test of

that series (none of the no balls were scored from), but there were several

instances in the second Test. The change

became permanent in Test #1424, Pakistan v Aus, Oct 1998. In the Zim Test, it is particularly interesting in that the

match was very close. In the final innings, the 8th wicket fell with 4 balls

left and 11 to win. At that point the tailenders decided not to go for

victory and played out the four balls. But if the scoring protocol had been

normal for that time, the target would actually have been 8 runs (and 7 to

tie), not 11. I wonder: perhaps they would have had a go at that. ******** From time to time

a batsman scores a century on the first day of a Test even though his team

batted second. Bowlers have also been known to take five or more wickets on

the first day, bowling second, but it has become rather rare in these days of

covered wickets and slow over rates. The most recent case is Glenn McGrath at

Lord’s in 2005. After Australia was out for 190, McGrath took five wickets

for two runs from his 4th to 9th overs, immediately

following tea. He finished the day with 5 for 21. ******** Fred Price

was a wicketkeeper from Middlesex who played one Test in 1938. He played 402

first-class matches without ever bowling, the all-time record for a complete

career. Kumar

Sangakkara played 529 List A games (and also 267 T20) without bowling.

However, he bowled in f-c cricket. T20: Eoin

Morgan has played 333 T20s to date without bowling. Combined

totals: Steven Davies, who has played for England and various counties, has

played 581 games (240 f-c, 188 List A, and 153 T20) without bowling. He

bowled one over in an Under-19 Test. He is still active. ******** |

17 August 2021 In response to

an enquiry, I put together a list of bowlers who have bowled underarm in

Tests. Gerald Brodribb actually wrote a book on underarm bowling. I don’t have a copy, but there is a

surprising amount of stuff on ‘lob’ bowling on the internet (Cricket Country

and elsewhere) that is probably derived from Brodribb,

at least in part. I have scoured this and come up with the following (some is

from notes in my database). Most of these were bowling lobs, and the underarm

part is presumed. Hornby is an exception, bowling "grubbers". Underarm bowlers in Tests T Armitage Eng v

Aus (1), Melbourne (MCG) 1876/77 AN Hornby Eng v

Aus (1), Melbourne (MCG) 1878/79 WW Read Eng v

Aus (1), Melbourne (MCG) 1882/83 WW Read Eng v

Aus (3), The Oval 1884 A Lyttleton Aus

v Eng (3), The Oval 1884 G Ulyett Eng v Aus (2), Melbourne (MCG) 1884/85 one ball

only AE Stoddart Eng

v Aus (4), Melbourne (MCG) 1897/98 GHT

Simpson-Hayward Eng v SAf 1909/10 Five Tests Simpson-Hayward

is regarded as the last of the regular lob bowlers. Test players recorded as bowling

underarm in first-class cricket but not in Tests For the most part, these players did so only once,

or on rare occasions. EM Grace SMJ Woods CB Fry R Spooner GF Vernon LCH Palairet RH Spooner EG Wynyard JM Blackham H Verity JB Iverson JM Brearley CF Root G Brown Yuvraj of

Patiala Dilip Vengsarkar is said to have bowled an over of lobs for

West Zone against the MCC in 1984-85. However, these appear to have been

‘donkey drops’, not underarm. I read also the

Hornby was also ambidextrous with regard to bowling. Apart from him, I have

not seen any references to bowling ‘grubbers’ (as opposed to lobs) in Tests. ******** Dismissal Frequency by Ball of

Over Is there any

pattern to dismissals according to which ball of an over is being bowled? I

decided to have another look at this. For all dismissals in Tests from 2003

to 2020, the numbers are

This

distribution is largely random. There is a slight shortage of dismissals on

Ball #1, which seems to be associated with a pattern in tail-end dismissals.

There is an excess of 8th-10th wicket dismissals toward the end of an over,

perhaps because of failed strike-farming attempts. For the first

seven wickets, where the innings continued after the dismissal, the numbers

are

This is a fairly

random set of numbers. None of these numbers is even 1 percentage point away

from the mean of 16.67%. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

13 July 2021 I have updated the Hot 100 list – the fastest-scoring Test batsmen.

It’s been a couple of years since the last update. Most batsmen

tend to score at a characteristic rate which varies less, over time, than

batting average. The upshot is that the list changes only gradually, apart from new players making an

appearance, so it doesn’t matter too much if updates are infrequent. It is

interesting though that David Warner, still very prominent in the list, has

been ‘calming down’ to some extent in recent years. He sometimes plays

defensively now (only sometimes). His career scoring rate as of 2019 was

74.5; this has now dropped to 72.7. His scoring rate in the interim has been

62.5 runs per 100 balls, and that includes his triple-century against

Pakistan. The full lists

are at the usual link. I have also prepared

the list below, restricted to fully-recognised batsmen, just to see how the

list looks without the lower-middle-order all-rounders and wicketkeepers who

are prominent on the full list. The list is filtered simply by restricting to

batsmen with an average batting position of less than 6.1. (All innings for

such batsmen were included, even below #6 position, as long as the career

average position was 6.1). The runs qualification has been raised to 2000

career runs for modern batsmen, although it remains at 1000 runs for earlier

times. Given these

qualifications, Virender Sehwag’s lead becomes very striking indeed. Shahid

Afridi was faster still as a top-order player, but his Test record is rather

patchy and he never reached 2000 runs. Fastest-scoring Test batsmen: ‘recognised’ batsmen

A modified version of this list, with adjustment for

changes in runs-scoring standards over time, is

available at the link. This particular list has not been

updated since 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During a tour

of Sri Lanka in 1996, Alistair Campbell and Henry Olonga

of Zimbabwe were swept out to sea while swimming, and had to be rescued by

lifeguards. The incident was reminiscent of a rescue during the rest day of

the Bridgetown Test of 1977, when Pakistan players Zaheer Abbas and Wasim

Bari were rescued from drowning while attempting to swim back to their hotel

from a raft that had drifted out to sea. ******** |

21 June 2021 Well it’s been a while since anything was posted.

Put that down to other work coming in (non-cricket) and general lassitude. It

might not be a reasonable response, but the effect of all these crushing

lockdowns has been to discourage rather than encourage me. Nevertheless,

Test matches are still being posted in my database – well into 1996 now. I

have been making minor (but painstaking) corrections to some older data too,

mostly in the session-by-session and ball-by-ball files, which did not always

line up precisely, particularly for inter-War Tests. Thanks to Glenn Timmins

for pointing out the problems. Anyway. Here are

a few items… Players making the greatest number of different

scores,

from 0 to 100, in all Internationals combined. It is not surprising that

Tendulkar leads here, but he never made scores of 58 or 75. A pity then that

he was out for 74 in his last Test; he had already made that score three

times. He also made two 76s late in his career. Tendulkar did

make scores of 58 and 75 in first-class cricket, although he never made 99 or

102, and a few other scores below 90, including 87. He did make those scores

in List A. If my search is correct, the lowest score (f-c and List A

combined) that Tendulkar never made is 129, followed closely by 130.

******** Batsmen who

faced 100 balls in a Test innings – highest career percentages. H Sutcliffe 58.3% of innings B Mitchell 52.5% WM Woodfull

51.9% DG Bradman 50.0% IR Redpath 50.0% L Hutton 50.0% KF Barrington 49.2% EAB Rowan 48.0% G Boycott 45.6% GM Turner 45.2% RS Dravid 45.1% (minimum 50 innings; some

estimates – a limited number – are necessary for older data) ******** Some stats on 20 (+) run overs in Tests. There have been

178 known instances of which 27 were in 8-ball overs. Of the 178, 96

occurred in this century. Of the 178, 118

included an individual batsman making 20 or more runs. In the others the runs

were shared or there were extras to make up the 20. Bowlers

conceding 20 in an over... four times for JR Thomson and MJ Hoggard. Two of

Thomson's were 8-ball overs. Three times by Swann, M Morkel, Boje, Willis and Sobers (Willis and Sobers include 8-ball

overs) Batsmen hitting

20 runs in an over: Gilchrist 6 times, Lara and Botham 3. Thirteen batsmen

have done it twice. Botham and Lara were also in one additional over each

worth 20 or more runs, although they did not themselves score 20. David

Warner has batted in four 20+ overs, although he has scored 20 runs only once

himself. ******** Here are some

percentages for 'No Play' days in Tests, by country. Days can be lost for a

variety of reasons but mostly weather. Abandoned matches not included, but

all other Tests are. Ireland 20.0% (1

match only) Bangladesh 5.6% New Zealand 4.8% England 4.2% India 3.2% Sri Lanka 3.0% South Africa

2.7% Zimbabwe 2.2% Australia 2.0% Pakistan 2.2% West Indies 1.9% UAE 0.6% (1 day

lost, following death of PJ Hughes) ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although he

was selected as an opening batsman, Roger Twose did

not get to bat until the fifth day of his second Test match. His debut at

Chennai in 1995 was washed out with only 2 sessions of play, and New Zealand

did not bat. The following Test at Cuttack was similarly afflicted, and New

Zealand did not bat until the morning of the fifth day. ******** I have

mentioned before that when Garry Sobers hit the ******** |

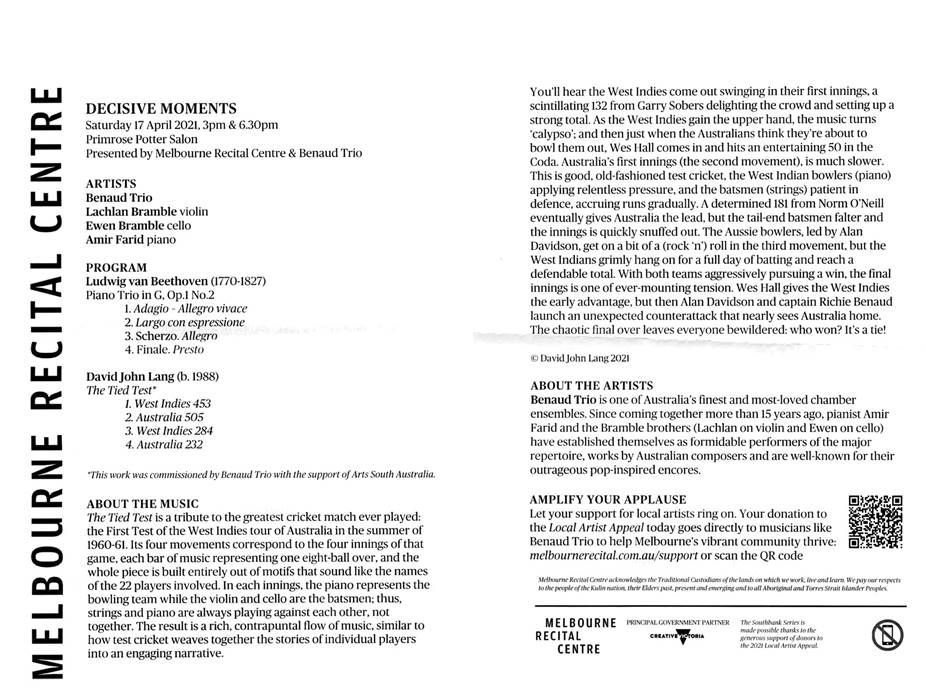

28 April 2021 Musical Cricket I had an unusual

'cricket' experience recently. I went to a concert by a classical trio

(piano, violin, cello) who call themselves the Benaud trio. They played a new

piece by David Lang called "The Tied Test". As a musical concept,

it is possibly unique. It was literally

a Test match (the Brisbane Tied Test in 1960) set to music. It had four

movements, one for each innings, with each over of the match corresponding to

one bar of music. Moreover, each of the 22 players was represented by a small

motif which was played while they were bowling (piano) or batting (violin,

cello). The players explained a few of these motifs before the performance;

they were linked to the players’ names, so “Richie Benaud” had four notes and

“Alan Davidson” five, with rhythms similar to the spoken name. “Wes Hall” had

just two notes, but played heavily to suit a fast bowler. I could not make

out all 22 motifs, of course, but I am sure I heard “Norm O’Neill” frequently

during the second movement. O’Neill of course scored 181 in the corresponding

innings. I had made a small

contribution to this. David Lang contacted me a few months ago about his

idea, and I supplied with all the statistical information I had on the Tied

Test. I regarded the

music as a great success. It had a calypso flavour, and was much more

accessible than typical modern music. It was the first

concert I have been to in 18 months, so was particularly memorable. It was a

small venue, perhaps 100 seats, but was sold out. There was no social

distancing. Masks were encouraged but not mandatory; about 20% of patrons

wore them. I must find out

how the Benaud Trio got its name. The name is serious; the group has been

around for 15 years and has won various chamber music competitions and

awards. There is a clip

of the composer explaining the music at the link (I get a mention) https://www.facebook.com/benaudtrio

******** I did an

interview last week with Jack Snape of the ABC, discussing aspects of the

history of cricket scoring. We covered a range of subjects and it was quite

enjoyable. It is a bit unfortunate, though, that they focussed on that old

Bradman four runs thing, an article that I wrote 13 years ago, and is old

news. https://www.abc.net.au/.../sir-don-donald.../100078546 For the record,

I still stand by the analysis of Bradman. However, moving the mystery four

runs (in the final Test of 1928-29) into the Bradman column is only one of a

number of possible resolutions for the anomaly in the surviving scorebook,

and I would concede it is not the most likely. It is still an open question,

though. ********* 333 with no 3s It’s a rather

large and fiddly table, but for anyone interested here is a complete

breakdown of scoring strokes for all Test triple (or should that be treble?)

centuries. It’s fair to say that all such innings benefit from benign batting

conditions, but how could it be any other way? If a batsman could score a

triple under difficult conditions, what should he be capable of when the

going is good? There is quite a

lot of variability in the composition of the strokes. This can reflect the

speed of the outfield or the batting style, or both. It can be hard to

unravel these factors. Undoubtedly, Chris Gayle benefited from a small ground

and fast outfield when he hit 333 at There is a quite

a remarkable difference between the triples by Edrich

and Cowper, made within months of one another. Edrich

hit 57 boundaries and 3 threes, while Cowper hit 20 boundaries and 26 threes.

Cowper’s 307 was scored on a large ground with extremely slow outfield: his

fours included several that were all-run. One can speculate that Cowper’s

innings might have been worth an extra 50 runs under the conditions enjoyed

by Edrich.

†Hammond’s

official score is, of course, 336 not out, but re-scoring the scorebook gives

him 337 not out. I have used the latter so that the strokes add up. Incidentally,

the highest innings for which I do not have a full stroke breakdown is the

next on the list – Bradman’s 299* at Adelaide in 1931-32. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

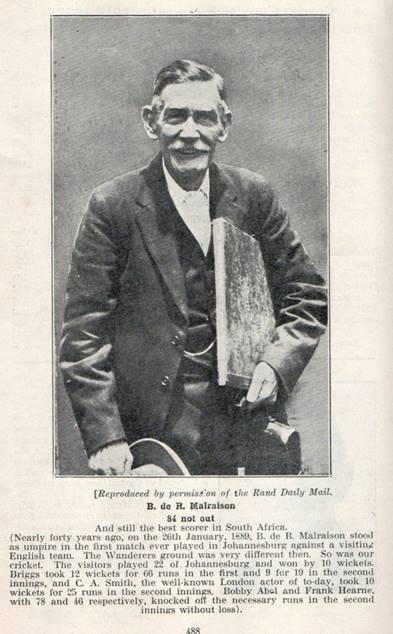

26 March 2021 A Lost Century? In the previous

post I mentioned the discovery of scores from the 1909-10 M.C.C. tour of

South Africa. I have now rescored these matches into ball-by-ball form and

they have been posted in my online database here. Robin Isherwood

has provided more information on the source. The scorebook was the work of

one Bernard de Rockstro Malraison

(1844-1930), a long-time scorer in Transvaal. He had stood as an umpire in a

match involving Major Warton’s team in 1888-89, but not in the Tests. He is

not to be confused with his son W. de R. Malraison

(1876-1916) who played for Transvaal a couple of times. The younger Malraison died fighting in the Great War, not in Europe

but in East Africa, where there was considerable conflict between British and

German colonials. In the

scorebook, the first three Tests are in the same hand, almost certainly Malraison himself. The scores are accurate and re-scoring

was straightforward. The fourth and fifth Test scores, played in Cape Town,

are in a different hand. The scorers are identified as W.W.A. Colson

(1884-1941) and T.H.G. Lancellas (1874-1934). These

later scores contain problems. They are almost certainly re-copies, and

errors have crept in, some of them significant. For instance, in South

Africa’s 103 in the final Test, there are 33 extras recorded. These extras,

however, apply to England’s first innings of 417. An unusual

feature of newspaper reports of the final Test include statements that there

was an error in the scoring of Aubrey Faulkner’s 99 in the second innings,

and that he actually scored 100; it was said that one run had been mistakenly

credited to Sinclair (37). And indeed, the re-score does give Faulkner an

exact 100 and Sinclair 36. Unfortunately, it is not clear-cut. There are

several anomalies that occur in the score during the innings; for example,

Faulkner’s scoring stroke order in the batting score does not match the

bowlers’ rescore analysis. So, uncertainty must remain; I would say, though,

that when I tried a few possible changes to the bowling (which itself creates

new anomalies), Faulkner still gets his 100. Robin Isherwood

also sent me a photo of Malraison with his

scorebook, taken when he was 84 years old. It is rather charming and I will

post it here…

******** A New Look at the

‘Slowest’ and ‘Quickest’ Bowlers I have done a

little exercise to look for the current bowlers who are fastest and slowest

in getting through their overs. I was able to do this thanks to Benedict Bermange,

who has over the years sent me quite a number of his linear Test scores with

clock times at the start of every over. I have entered this data onto a

spreadsheet for 22 recent Tests (since 2019, more than 7000 overs). Benedict

only scores Tests involving England, but the 22 Tests involve all the major

Test countries. Bowlers who did not play against England in this period are

not covered. I was inspired

to do this by a comment from Benedict that Ishant

Sharma seems to take an inordinate time to get through his overs. And sure

enough, guess who tops the list of 67 'slowest' bowlers, and by a significant

margin? Bowler minutes per over I Sharma 5.56 ST Gabriel 5.07 MA Starc 5.03 JL Pattinson

4.98 JJ Bumrah 4.90 AA Nortje 4.85 MA Wood 4.83 PJ Cummins 4.80 JR Hazlewood 4.69 Shaheen Shah

Afridi 4.65 Times are given

in fractions of minutes, not minutes:seconds. The calculation

only considers what I call 'standard' overs, or complete overs without

interruptions. (Standard overs comprise about 82% of all overs.) Overs with

wickets, reviews, drinks break, injuries etc are filtered out. Leaving them

in doesn't affect the order much. The bowlers who get

through their over the quickest, based once again on uninterrupted overs, are NM Lyon 3.50 S Nadeem 3.45 RL Chase 3.41 Yasir Shah 3.39 RRS Cornwall

3.34 JE Root 3.34 KA Maharaj 3.31 R Ashwin 3.23 JL Denly 3.21 AR Patel 3.17 Although Akshar Patel has the fastest standard over, he ranks only

about 10th on an 'every-over' basis. This reflects the very high frequency of

wickets that he has taken to date, which increase over times by about 1.5

minutes each time there is an interruption. The

qualification is minimum 25 'standard' overs. Benedict's clock times only go

to the nearest minute, but when averaged out, more precision is possible. I also looked at

the effect of interruptions of various kinds on minutes taken to bowl an

over.

******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Most runs off

6 consecutive balls in Tests… The record for

a single over is 28, but three batsman have scored 29 off six consecutive

balls spread across multiple overs: Adam

Gilchrist 664616 during his famous Perth century; Andy Blignaut 646661 at Cape Town in 2005. ******* The player

involved in run outs most times in ODIs is Mohammad Yousuf 79 times (run out

38 times, partners 41). Steve Waugh is on 78 (27+51) and on 76 there is Inzamam (40+36) and Sachin Tendulkar (34+42). Run out

most times is Marvan Atapattu on 41 (+24

partners),while for partner run outs the record is Waugh (51, above). There is

uncertainty in some of the above figures for partners. I suspect that there

are errors in fall-of-wicket batsman identifications in older matches. I have

never checked the 'official' identifications in ODIs but I believe that some

of them are guesswork. I have surveyed the equivalent data in Tests and found

more than 400 errors in the 'official' online scores. ******** From Arnold

D’Souza: ******** |

13 March 2021 Falling at the Last Here is a list

of batsmen who batted all day only to be out to the last ball of the day. I

prepared this when I noticed that this fate had recently befallen two English

batsmen in the space of only a few Tests. Almost 200 Tests had passed since

the previous instance in 2016. Batsman (final score)...number of

runs, day, Test H

Sutcliffe(161)…141, day 3, Eng v Aus (5), The Oval 1926 CA

Roach(209)…209, day 1, WI v Eng (3), Georgetown, Guyana 1930 Pankaj Roy(140)…140,

day 1, Ind v Eng (2), Mumbai (Brabourne) 1951/52 Pankaj

Roy(150)…120, day 5, Ind v WI (5), Kingston, Jamaica 1953 Waqar

Hassan(189)…154, day 3, Pak v NZ (2), Lahore (Jinnah) 1955/56 Khalid Ibadulla(166)…166, day 1, Pak v Aus (1), Karachi (National)

1964/65 ED Solkar(67)…67, day 3,

Ind v Eng (1), Lord's 1971 GM

Wood(126)…126, day 4, Aus v WI (3), Georgetown, Guyana 1978 SM

Gavaskar(115)…115, day 1, Ind v Aus (4), Delhi (FSK) 1979/80 MD Crowe(137)…123, day 3, NZ v Aus (2), Christchurch

1985/86 MH

Richardson(99)…99, day 1, NZ v Zim (2), Harare

2000/01 MP

Vaughan(177)…177, day 1, Eng v Aus (2), Adelaide Oval 2002/03 AN

Cook(105)…105, day 1, Eng v WI (3), Bridgetown, Barbados 2015 TWM

Latham(136)…136, day 1, NZ v Zim (2), Bulawayo

(Queen's) 2016 JE Root(186)…119,

day 3, Eng v SL (2), Galle 2020/21 DP

Sibley(87)…87, day 1, Eng v Ind (1), Chennai (Chepauk)

2020/21 Qualifications: more

than 50 overs in the day and the match had to continue next day after the

batsman was out. In the Solkar and Crowe cases, the team was all out, so it is

very likely that the day’s play would have continued if the wicket had not

fallen. Of the above, only

Waqar, Ibadulla, Gavaskar and Taslim were out to

the last ball of an over, so presumably these are the only ones who knew they

were facing the last ball of the day. This is not absolutely certain, since

there could have been another over if they hadn't been out. However, in the Ibadulla and Gavaskar cases, it is known that no further

overs could have been bowled. ******** Here are lists

of the fastest and slowest Test partnerships, in terms of speed for the first

100 runs. The data is drawn from the ball-by-ball database, supplemented,

where ball-by-ball data is absent, by research into original reports.

Overall, time or balls faced information was found for the first 100 runs for

about 95 % of century partnerships. Generally speaking, where data is absent,

the partnerships were not remarkable in terms of speed (or lack of it). In some cases,

conversions had to be made between minutes and ball bowled, using over rates

for the relevant innings. This creates a little uncertainty in the exact

rankings in the following tables, particularly the first table where changes

of only a couple of minutes could affect results. The fastest

times in minutes (and the slowest in balls bowled) are mostly from older

Tests, played in the days of high over rates. By contrast, when it comes to

fast partnerships in balls bowled, recent Tests dominate. Fastest Test Century partnerships (1st

100 runs, minutes)

Slowest Test Century partnerships (1st

100 runs, minutes)

Fastest Test Century partnerships (1st

100 runs, balls)

Slowest Test Century partnerships (1st

100 runs, balls)

None of the partnerships in the final category would

rival the partnership of 98 by Sardesai and

Manjrekar at Bridgetown in 1962, which occupied close to 590 balls and 248

minutes. I may add these

lists to the Unusual Records section. ******** Andrew Samson

has come up with some ‘new’ Test match scores, found at the Johannesburg

Wanderers ground. They are from a handwritten scorebook, by a gentleman named

Malraison, that has somehow survived the years. It

contains, among other things, full scores for all five Tests of the 1909-10

M.C.C. tour of South Africa, Tests that were previously lost. Breakthroughs

like this have become rare, made even more difficult by the restrictions

related to the Covid virus. So this is a great find, and Andrew has kindly

already supplied me with copies. I will re-score it into ball-by-ball form in

due course. Credit to Robin

Isherwood, who alerted me to the existence of this book, and the possibility

of it containing Test match scores, 15 months ago. It took a sustained effort

by Andrew to get access to the book. ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The

responsibility for calling no balls in internationals has now been fully

handed over to the third umpire. The change was introduced when Test matches

re-commenced in England last July. In 18 Tests since then, there have been

199 no balls called. In the previous 18 Tests, when the calls were left to

on-field umpires or referrals, there were only 77 no balls. This is quite

a significant change! ******** Most runs by

a batsman off a single bowler in an ODI… at the SCG in the 2015 World Cup, AB

de Villiers (162*) scored 76 runs off JO Holder. Note: this was NOT de

Villiers' record-breaking 100 in 31 balls innings. ******** Carl Hooper

took 568 balls to progress from 99 Test wickets to 100, spanning three Tests

in 2001. ******** (As of end of

January) In the last 19 Tests, only one has been won by the team winning the

toss. Three draws and 15 losses. In the sole victory (NZ v Pak at

Christchurch) the team winning the toss (NZ) chose to bowl. It certainly does

fluctuate. In the previous 19 Tests, there were 11 wins to the team winning

the toss, and 5 losses. Back in 2018 there was a sequence of 13 consecutive

wins to teams winning the toss. ******** How did underarm

bowling really work?... Before about

1750 cricket bowling was literally bowling, that is all along the ground.

Lumpy Stevens, it is said, invented ‘length’ bowling. I don't

really know about the specific actions, but according to Barclay's World of

Cricket A-Z, most bowling before 1800 was "medium to fast". A

bowler named Lamborn was the first off-spinner. From 1777, a bowler named

Noah Mann was "giving a curve to the ball the whole way". About 50

years ago my club played a game against a team of blind cricketers (legally

blind, but most could see a bit). The ball was made of wicker with a bell in

it, and the bowlers bowled underarm. You had to pitch the ball in the first

half of the pitch, and the ball, ringing, would bounce several times. The bowlers

had a run up and sent the ball down surprisingly fast. The stumps were bright

orange (for those who could see a bit) and had a bell attached which the

keeper would ring to orient the bowler and assist returns from the fielders.

We did sometimes help fielders who couldn't find the ball when it stopped

moving. They

absolutely thrashed us, as I recall. Certainly the most memorable cricket

match of my youth. ******** The

Australia/India series really went down to the wire, with the series result

very much in the balance going into the last hour of the last Test. I

couldn't find any precedents in series of 4 or more Tests, where the final

Test produced a result. It has

happened occasionally with 3-Test series. In 2013-14 in South Africa,

Australia won the final Test with 6.4 overs left, to take the series 2-1. In West

Indies in the same season, New Zealand won the final Test with 13.4 overs

left, to take the series 2-1. ******** Highest

innings in Tests that were both unbeaten and completely chanceless… Lara's 400*

contained 'technical', 'half-' or 'possible' chances only. Warner's 335*

against Pakistan last year was chanceless but there was one DRS and he was

caught off a no ball on 236. In the DRS era,

Adam Voges 269* against West Indies was chanceless and there were no reviews

or run out attempts. Javed

Miandad's 280* against India in 1982-83 was chanceless. All other unbeaten

innings higher than this prior to 2000 are known to have included chances of

some description. ******** Usman Shinwari of Pakistan has played in 17 ODIs but has faced

only seven balls in his four innings. His one and only scoring shot was a

first-ball six off Marcus Stoinis in 2019. He was

out next ball.

|

7 February 2021 Dropped Catches Report 2019-2020 I have updated

the survey of dropped catches in Test matches to include matches up to the

end of 2020. As I have reported in the past, the list is created by searching

Cricinfo’s (vast) ball-by-ball texts for mentions

of missed chances, searching for up to 40 terms (or euphemisms) that are used

to indicate chances. This usually whittles the texts down to about 100 ‘hits’

per Test, which I then read through to identify real chances. The continuous

survey goes back to late 2001, plus some Tests from the previous 12 months.

The first two or three years have gaps, in that the texts sometimes lacked

the necessary detail. (I also have very patchy data on Tests from the 1920s

to 1990s from other sources, which I have reported on elsewhere.) I have combined

the data from 2020 with 2019 since the number of matches in 2020 was so

limited. Overall, 24.1% of chances were missed in this period, including

missed stumpings but not missed run outs (run outs are not searched). This

represents 6.26 missed chances per Test. Since 2002, the average rate has

been 25.6%, so 24.1% represents a better than average year from the fielders’

perspective; However, the rate was higher than 2018’s 22.6%, which was the

lowest recorded. Overall the rate

from 2002 to 2010 was 26.0%; from 2011 to 2020 it was 24.9%. This indicates a

gradual, if slight, improvement in catching. This appears to be an extension

of a long-term trend; data from earlier decades, where available, indicated

rates of 27-30%. The data

breakdown for the various countries is shown in the table. Overall, South

Africa has had the best catching record, although there are signs of decline

in the most recent data. For some years, South Africa had Boucher keeping

wickets and Graeme Smith at slip; both of these players had outstanding

catching records, as did AB de Villiers. Recent

improvement in catching by Pakistan is quite striking and appears to be

sustained. Is it something to do with the UAE grounds?

The usual caveats

apply to this data. Chances described as “half”, “technical” and “academic”

are included. Whether or not an incident counts as a missed chance can be a

matter of opinion; I do think, however, that up to 90 per cent of chances

would be agreed by nearly all observers. The data also depends on the

completeness of the Cricinfo texts and the efficiency of the search. It would

be nice if the Cricinfo commentators would use a single indicator phrase to

flag misses; they often use DROPPED in upper case, but there are many

exceptions that have to be uncovered by deeper searching. As for bowlers

who have suffered the most, it is a two-horse race. Jimmy Anderson is

currently on 122 and Stuart Broad 120, well ahead of Harbhajan Singh on 99.

Note that Tests this year have not been covered. Spare a thought for Pakistan

spinners Danish Kaneria and Saeed Ajmal, who have suffered drop rates of 39

and 40 per cent respectively off their bowling. Spinners often have higher

rates because many of their chances are caught and bowled or short leg, or

‘reaction’ wicketkeeper catches. Alastair Cook

completed his career with 78 missed chances off his batting, a number that

will take some beating. Sangakkara and Sehwag are next on 67; Sehwag’s miss

rate as batsman of 37 per cent is the highest among major batsmen. Cook is also the

‘leading’ fielder, missing 81 chances, or 32 per cent. He spent a lot of time

fielding at short leg, where catching is difficult and often a matter of

luck. A more detailed

article on this subject from 2016 is here. ******** Did Bradman know he needed just four runs in his last Test, to

average 100? Bradman said he

didn’t, in unambiguous terms: But did anyone

else know in advance? There is no apparent evidence. Looking at

Trove, I could not find any mention of Bradman needing four runs to average

100 in any of the match previews just before the Test. Some previews mention

him needing 83 runs to reach 2000 for the English season, and 674 (on the

rest of the tour) to reach 10,000 career f-c runs in England. Bradman's 6996

runs, and his average as it stood of 101.39, can be found in isolated reviews

of the fourth Test in the Newcastle Morning Herald and in the Melbourne

Herald. Even this doesn't seem to have been widely noticed, and the

implications for the final Test were not discussed. It’s worth noting that

anyone pondering the question in advance would have presumed that The Don

would be batting twice at The Oval, in which case he would have needed 104

runs (if he was out twice). https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/140342748?searchTerm=bradman%206996# https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/247298602?searchTerm=bradman%20average By the end of

the fifth Test, Bradman’s shortfall had been noticed in multiple

publications. Even before the final day, an article in the Brisbane

Courier-Mail remarked that Bradman was four runs short. It was evident at

that point that Bradman was not going to bat again, as England was going to

lose by an innings and plenty. It is

interesting that some sources at the time were reporting Bradman's career

average as 89.7. That was his average against England. There was still

widespread opinion in those days that the only 'real' Tests were Ashes Tests. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/49918364?searchTerm=bradman%20average ******** |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Here is some

data concerning the percentage of batsmen out ‘clean’ bowled versus 'played

on'. I have conducted a little survey of the last 100 Tests, to come up with some

figures. (Caveats:

this depends on the accuracy of the Cricinfo texts and my ability to

interpret them.) Total out

bowled: 554 Hit bat

first: 121 Hit pad/body

first : 24 Some (not

quantified) hit both the bat and the pad. Bonus stat... Batsmen bowled

offering no stroke = 26. This includes some cases where the batsmen tried to

withdraw the stroke but the ball hit the bat anyway. It would also

be interesting to know how many batsmen are playing on to balls that would

not have hit the stumps, but that is not feasible with text data. ******** Bowlers on

debut whose first two balls were hit for four, a very short list… Roy Gilchrist

1957 Dinusha

Fernando 2003-04 Navdeep

Saini, SCG 2021 I was surprised

that I couldn’t find any more cases than this in the database. ******* |

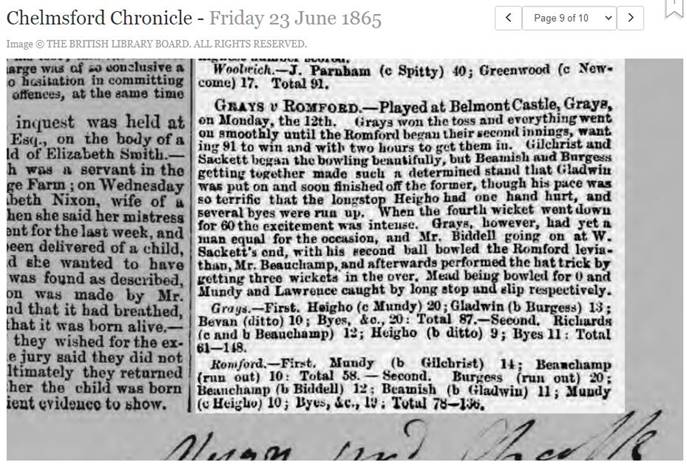

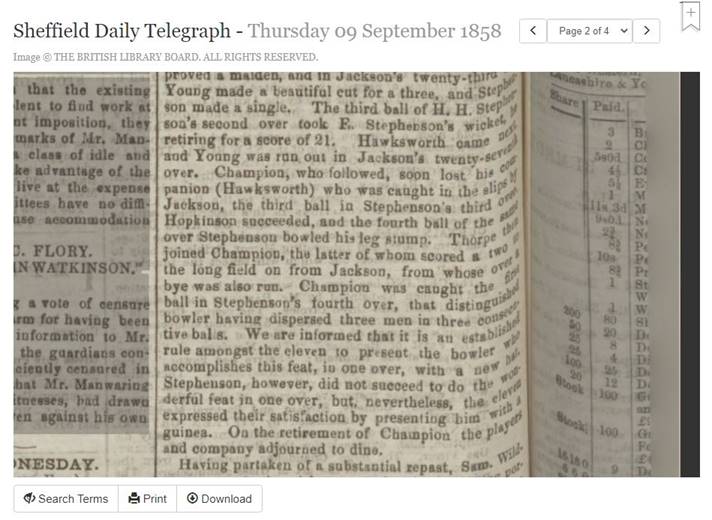

9 January 2021 A few notes on the

origins of ‘hat-trick’… I was looking at

various sources that discuss the origin of the term. They have a tendency to

either repeat one another, or sometimes contradict one another without

explanation. I decided to look to see if there are some truly original

sources to be found. The concept of a

hat-trick is said to have its origins when HH Stephenson took three wickets

in three balls in a match in 1858, and was presented with a new hat for his

troubles. However, the term ‘hat-trick’ (or ‘hat trick’) doesn’t seem to

appear in print in newspapers until 1865, in the Chelmsford Chronicle in

Essex.

This reference

is mentioned in Wikipedia. I did my own search of the British Newspaper

Archive, and found this independently; it was earliest reference that I

found. The Stephenson

1858 link to hat-tricks has been reported many times. I was curious about

sources, and tracked down the actual origin match, an Eleven of All England v

Twenty-Two of Hallam and Staveley at Hyde-park, Sheffield on 6, 7 and 8

September 1858. The Eleven was a team of professionals touring around

England; the inimitable Julius Caesar was in the team. Stephenson’s triple

hit occurred on the last day, as recorded in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph.

There are a

couple of interesting elements to this original report. Firstly, that the

presentation of a hat was already a “custom” in this team, as long as the

three wickets occurred in the same (four-ball) over, and secondly, that

Stephenson was not actually presented with a hat after all! His trick was

spread over two overs, and so did not qualify for a hat, but it was

sufficiently noteworthy for the team to present him with a guinea (21

shillings) presumably after a whip-round. It is not clear how many, if any,

hats had previously been awarded through this ‘custom’. Hat-tricks were

uncommon even then, and we are talking about just one team. But as we have

seen, the actual term ‘hat-trick’ was not yet in use. We can see where the

‘hat’ comes from, but why ‘trick’? Searches show that the term was already in

use in reference to magicians and magic shows, and this may have rubbed off

on cricket. A search of

Trove in Australia turns up quite a few occurrences of the term in the early

to mid 1870s, but always in relation to magic. The

first Australian cricketing reference is found in December 1877. The

hat-trickster was Harry Boyle, and he was indeed presented with a new hat!

This took place during an early match on the epic 1877-1878 tour by the

Australian XI, playing against 22 of Newcastle in New South Wales.

Perhaps the

term, and the custom of presenting a hat, was brought to Australia by Shaw’s

team earlier that year. However, it doesn’t seem to have been applied during

Shaw’s matches: perhaps there were no actual hat-tricks. There are a few

occurrences in 1876-77 for phrases like “three wickets in three balls”, but

all are in minor matches not involving the tourists, with no mention of hats. ******** Note the UPDATE

below on the subject of international cricket broadcasts. |

*****